| Hila Ben Abraham, hila@wustl.edu (A paper written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) |

Download |

CCNx synchronization protocol is part of the current CCNx implementation, and is

used to synchronize data collections over neighbor hosts running the CCNx

application.

In this work we explored the CCNx synchronization performance. Our main goal was to

evaluate the time it takes to synchronize different items over different topologies

that share the same collection. We designed and performed a set of experiments to

measure the synchronization time in seconds, and we used performance analysis methods

to determine which factor has the significance effect on the synchronization times.

In this work, we evaluate the performance of the CCNx synchronization protocol. This section describes the background knowledge of the NDN and the CCNx projects.

Named Data Networking (NDN) [Zhang10] [Jacobson09] [Jacobson11] is a recently suggested Internet architecture that efficiently supports content distribution. Unlike the current Internet architecture, NDN takes the content-centric approach [Perino 2011] by delivering a packet according to its content rather than to a pre-defined destination address. To receive data, an NDN host expresses an interest packet that contains the requested data name (label). The NDN network forwards the interest packet to the next hop by looking into the forwarding table, finding the longest name match, and sending the interest to the attached face [Haowei12]. The NDN host responds to an interest packet by sending a corresponded data packet. In the NDN architecture, a single data packet is sent to each received interest packet. In addition to the forwarding of interests and data packet, the network element (NE) stores the incoming data packets in its local content store (CS). On the reception of an interest packet, the NE first checks for the content in its local CS. If the content exists, the NE generates a data response that contains the stored information. If the content doesn’t exist, the NE forwards the packet according to the interest name.

Content-centric-networking project (CCNx)[ccnx] is a preliminary implementation of the content-centric networking approach. CCNx is an open source distribution developed by PARC. Because CCNx implementation includes the main attributes of the NDN architecture, it is considered to be the current NDN prototype. The NDN research group uses CCNx as the evaluation platform of the NDN architecture. In this work we evaluate the performance of the synchronization protocol [ccnx sync protocol], which is one of the CCNx published protocol.

The Open Network Laboratory (ONL) [onl] [Wiseman08] is an open and available network testbed, which can be used for networking research. Using the ONL interface, users can construct different network topologies, and explore the performance differences of these topologies. In this work, we used the ONL to construct 4 different topologies and to measure the synchronization protocol performance over these topologies.

In this section, we describe the main characteristics of the ccnx synchronization protocol.

The motivation behind the CCNx synchronization protocol is to keep a collection of information synchronized between 2 CCNx nodes. An example of a possible synchronized collection is a private music directory that should be kept up to date in a user’s smartphone and personal computer [Jacobson12]. Another example of possible synchronized information is the network graph that should be similar in all the network routers to enable the correct operation of common routing protocols such as OSPF and ISIS.

Unlike the common approach, CCNx synchronization protocol keeps a synchronized collection up to date by sending only the differences of the collection rather than the entire collection. The benefit of sending the differences over sending the entire collection is clear when it comes to the network traffic [Eppstein11]. This benefit becomes significant when synchronizing a large collection. However, the effect of synchronizing the differences on the synchronization time is unclear. In this work, we try to explore the synchronization times and to understand how long it takes to synchronize collections’ items over different network topologies.

The CCNx synchronization protocol consists of 2 protocols: CCNx Create protocol [ccnx create collection protocol] and CCNx Sync protocol [ccnx sync protocol]. The first is used to define and create the collection in the node repository. The second is used to synchronize the collections. In this work, we distinguish between these 2 protocols, and the reported numbers represent the measurements of the CCNx Sync protocol.

The CCNx software module that implements the Synchronization protocol is called the

Sync Agent. An instance of the Sync Agent runs on each of the participating CCNx nodes.

The Sync Agent keeps the collection content using a tree structure called the

sync tree. The Sync Agent updates the tree according to the changes in the

node’s local repository [ccnx repository]. Each node in the tree holds a combined

hash that represent the arithmetic sum of the individual names in that node, and the

combined hashes of the node children.

To stay up to date, each Sync Agent sends a periodic Root Advise

interests to all of its neighbors, including its root hash. On the reception of a

Root Advise interest, the Sync Agent checks if its local root hash is

equal to the remote root hashed. If not, the Sync Agent replies with its local

root hash. If the root hashes are equal, there is no reply to the incoming Root

Advise interest. When the Sync Agent receives a response to its Root

Advise, it compares the hashes, and sends Node Fetch interest to receive

the content of each different hash element. In case the content hash of the element

does not exist in the local collection, the Sync Agent expresses a regular

interest packet instead of the Node Fetch interest. Because of this behavior,

our experiments include an operation factor to distinguish between the creation of a

new element and the update of an existing element.

In this section, we present our experiment design. First we describe our experiment goals and metrics, and then we define our experiment parameters and factors. [Jain 91]

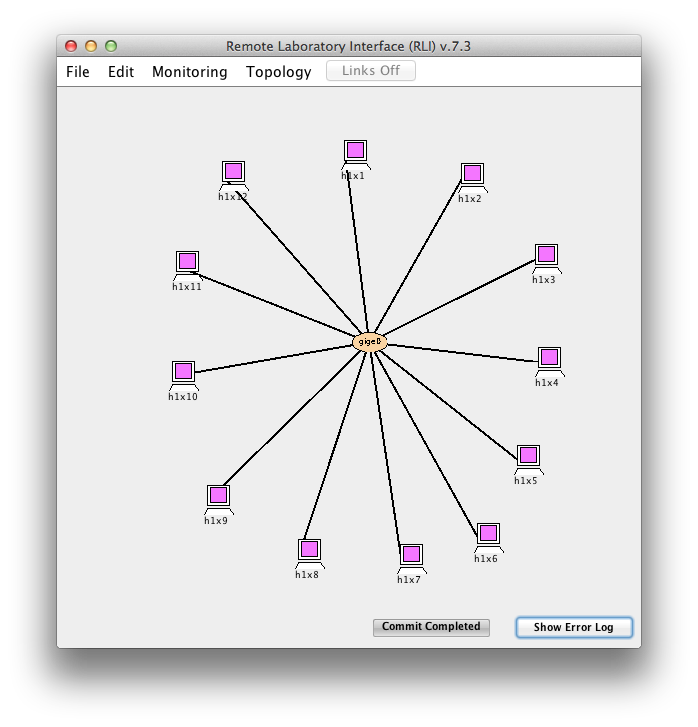

Since it is not possible to send real NDN packets, we used the ONL to create an overlay CCNx network on the top of a physical IP network.

Using the ONL interface, we constructed a physical network consisting of 12 Pc1core

nodes connected to a single virtual switch. In each experiment, we defined a different

overlay NDN network consisting of a different topology or a different scale. We

explored the synchronization times by adding or updating content into a collection in

one of the CCNx nodes, and measuring the time it took the synchronization protocol to

synchronize the new content over the entire overlay network.

Figure 1 shows our constructed physical network.

Figure 1. System physical network

The goal of this project is to evaluate the time it takes to synchronize content over different topologies and different scales using the CCNx synchronization protocol. Therefore, the appropriate metric is the time passed between the beginning of the collection update and the time the content appears in the last node. For a better understanding of the selected metric, we present the next example: a collection update operation starts at time x in node A, the content appears at time x+10 in node B, and at time x+12 in node C. In this example, C is the last node to receive the content, and therefore the reported measurement would be 12. In this work, the unit of the reported times is seconds.

As in other network systems, the measured performance can be affected by the system and the workload parameters. In this section we list these parameters as well as the selected factors and levels of our experiment.

As mentioned before, our study is conducted using the ONL. To construct the physical

network, we used pc1Core machines as the CCNx hosts, and one virtual switch to connect

them all.

To construct the NDN overlay network, we used the CCNx application and created UDP

routes between 2 CCNx hosts. Table 1 lists the System parameters.

|

Parameters |

Description |

|

Hosts Operating System |

Ubuntu 12.04.1 |

|

Host Memory |

1GB |

|

Host CPU |

2.0 GHz AMD Opteron |

|

Ethernet Interface |

1 Gbps |

|

Overlay Network Transmission Protocol |

UDP/TCP |

|

Number of physical hosts |

12 |

|

Number of virtual switches |

1 |

Table 1. System Parameters

For our measurement study, we designed and used synthetic workloads. Table 2 lists the workload parameters

|

Parameters |

Description |

|

Operation |

Insert new content or update existing content - Configurable |

|

Network scale |

Number of nodes participating in the topology - Configurable |

|

Network topology |

The network topology - Configurable |

|

Change size |

The content size – Configurable |

|

Transmission protocol |

Configurable |

|

Time between Create and Update operations |

Configurable |

Table 2. Workload Parameters

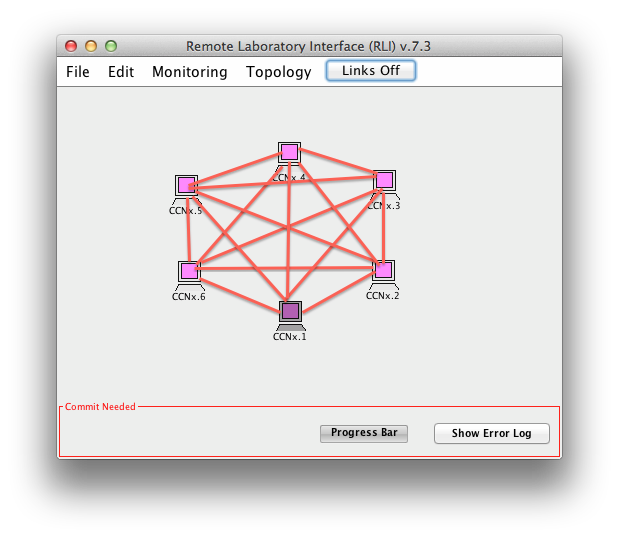

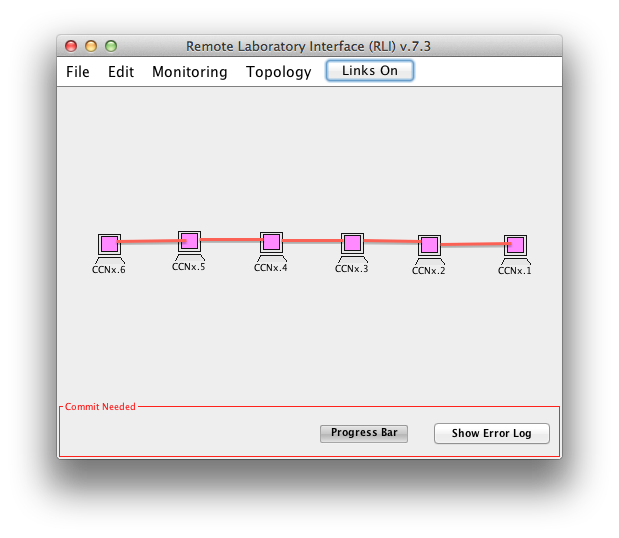

The factors of our performance study are listed in Table 3. The Operation factor determines the tested operation: Create new content or update an existing content. The Network Scale factor determines the number of CCNx hosts that share the same collection and participate in the synchronization process. The Network Topology factor determines one of 2 possible topologies: Fully connected mesh (figure 2) or chain (figure 3). In the Fully connected mesh topology, each CCNx host is connected to all the other CCNx hosts. In the chain topology, each CCNx host is connected only to the previous and following CCNx host. Moreover, in the chain topology, the first host is connected only to one follow host, while the last host is connected only to one previous host. The Content Size factor determines the size of the updated content. We distinguish between 2 different sizes: less than 1 MTU and more than 1 MTU. We decided on this parameter because of the NDN architecture behavior. In an NDN network, each content packet can contain up to 1 MTU bytes. Therefore, content that exceeds the 1 MTU limitation will result in the sending of additional interests and data packets. We wanted to explore the affect the 1 MTU limitation on the synchronization time, and therefore, we decided to include the Content Size as a factor in our experiments.

|

Factors |

Levels |

|

Operation |

Create / Update |

|

Network Scale |

6/12 |

|

Network Topology |

Fully connected mesh / chain |

|

Content Size |

Less than 1 MTU / more than 1 MTU |

Table 3. Factors to Study

Figure 2. NDN Overlay fully connected mesh topology

Figure 3. NDN Overlay chain topology

We developed a script that use the ONL interface, and define the CCNx overlay topology according to the configured factor. We used another script to perform an operation (Create/Update) on a selected CCNx host. In a shared log file, we saved the timestamp of the performed operation as well as the time the content got synchronized in each CCNx host. At the end, we calculate the differences of the synchronization timestamps and the operation timestamp, and reported on the larger difference.

As described, we used 4 factors, each of 2 levels. We used the 2^k*r method for our experimental design. In our study, k=4 and r=3. Table 4 lists the factors and the factors’ levels.

|

Symbol |

Factor |

Level -1 |

Level +1 |

|

A |

Operation |

Create |

Update |

|

B |

Network Scale |

6 |

12 |

|

C |

Network Topology |

Fully connected mesh |

Chain |

|

D |

Content Size |

64B |

76 KB |

Table 4. Factor Symbol and Levels

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the CCNx synchronization times. Table 5 presents the performance results. Then we list the data analysis and the factors’ affects and significant.

|

I |

A |

B |

C |

D |

Time (sec) |

Time (sec) |

Time (sec) |

Mean |

|

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

|

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

23 |

24 |

23 |

23.33333333 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3.666666667 |

|

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

|

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

17 |

16 |

16 |

16.33333333 |

|

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

23 |

23 |

24 |

23.33333333 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

6.333333333 |

|

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

24 |

7 |

23 |

18 |

|

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3.333333333 |

|

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

23 |

24 |

23 |

23.33333333 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

24 |

23 |

23 |

23.33333333 |

|

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

16 |

16 |

15 |

15.66666667 |

|

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

23 |

23 |

24 |

23.33333333 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

6 |

8 |

7 |

Table 5. Measured synchronization time

We performed 16 ONL experiments. We analyzed the data listed in Table 5 to determine what factors affect the system performance. Table 6 lists the statistical analysis.

|

Value |

Percentage (%) |

90% conf. interval |

Significant |

Important |

||

|

SSA |

2836.6875 |

80.57674441 |

-8.323129268 |

-7.051870732 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

SSC |

204.1875 |

5.799991715 |

1.426870732 |

2.698129268 |

Yes |

No |

|

SSAC |

143.5208333 |

4.076741447 |

1.093537399 |

2.364795934 |

Yes |

No |

|

SSBC |

88.02083333 |

2.500251505 |

-1.989795934 |

-0.718537399 |

Yes |

No |

|

SSAB |

88.02083333 |

2.500251505 |

-1.989795934 |

-0.718537399 |

Yes |

No |

|

SSABC |

50.02083333 |

1.420852985 |

-1.656462601 |

-0.385204066 |

Yes |

No |

|

SSB |

42.1875 |

1.198345396 |

-1.573129268 |

-0.301870732 |

Yes |

No |

|

SSBD |

3.520833333 |

0.10001006 |

-0.364795934 |

0.906462601 |

No |

No |

|

SSABCD |

1.6875 |

0.047933816 |

-0.448129268 |

0.823129268 |

No |

No |

|

SSCD |

1.6875 |

0.047933816 |

-0.448129268 |

0.823129268 |

No |

No |

|

SSD |

1.020833333 |

0.028997 |

-0.781462601 |

0.489795934 |

No |

No |

|

SSBCD |

1.020833333 |

0.028997 |

-0.781462601 |

0.489795934 |

No |

No |

|

SSACD |

1.020833333 |

0.028997 |

-0.781462601 |

0.489795934 |

No |

No |

|

SSAD |

0.520833333 |

0.014794388 |

-0.531462601 |

0.739795934 |

No |

No |

|

SSE |

57.33333333 |

1.628566187 |

||||

|

SST |

3520.479167 |

99.99940822 |

14.5935374 |

15.86479593 |

Yes |

|

Table 6. Factors affects and Percentage of variation explained

From Table 6, we can determine that the operation factor has the largest affect on the synchronization time. The Operation factor explains approximately 80% of the variation, while all the other factors and interactions explain the remaining 20%. From this table we can also determine that the errors percentage is relatively small, and explains only 1.6% of the variation.

In this project, we explored and measured the synchronization time of the CCNx synchronization protocol. We did 16 experiments and performed statistical evaluation of the synchronization times. Our data analysis shows that the operation type has the significant affect on content synchronization time. In addition, we discovered that different topologies as well as the network scale has no important affect on the synchronization time, at least in the scale range of 6-12 hosts per topology. As a result of the current ONL physical limitations, our current network topology and scale is relatively simple. To ensure our conclusion, more complicated and larger scale networks should be explored as part of the evaluation future work.

Furthermore, in order to understand and to explain the significance of the operation

factor, the future work should also explore the synchronization protocol implementation

and to clarify the differences between the creation of a new collection item and the

updating of an existing item.

As mentioned in the introduction part, in this project we focused on the

synchronization protocol performance. In order to understand whether the

synchronization protocol performance is better than a simple program used to

synchronize the entire data collection, a detailed comparison of the performance

analysis should be part of the future work.

NDN – Named Data Networking

NE - Network Element

CS - Content Store

CCNx - Content Centric Networking open source project

ONL - Open Network Lab

MTU - Maximum Transmission Unit

[Zhang10] Zhang, L. et al., "Named Data Networking (NDN) Project." Technical Report NDN-0001, NDN, 2010. http://www.named-data.net/techreport/TR001ndn-proj.pdf

[Jacobson11] “NDN from 50,000 feet” http://www.parc.com/work/focus-area/content-centric-networking/

[Jacobson09] Jacobson, V., Smetters, D. K., Thornton, J. D., Plass, M. F., Briggs, N. H., and Braynard, R. L., "Networking Named Content." In Proceedings of the 5th international conference on Emerging networking experiments and technologies, CoNEXT 2009. http://conferences.sigcomm.org/co-next/2009/papers/Jacobson.pdf

[Haowei12] Haowei Yuan, Tian Song, Patrick Crowley, “Scalable NDN Forwarding: Concepts, Issues and Principles”, ICCCN 2012, http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~yuanh/publications/2012_Yuan_ICCCN.pdf

[ccnx] Project CCNx, https://www.ccnx.org/

[Perino 2011] D. Perino, M. Varvello, “A reality check for content centric networking”, ACM Sigcomm Workshop on Information-Centric Networking (ICN) 2011, http://conferences.sigcomm.org/sigcomm/2011/papers/icn/p44.pdf

[ccnx sync protocol] http://www.ccnx.org/releases/latest/doc/technical/SynchronizationProtocol.html

[ccnx create collection protocol] http://www.ccnx.org/releases/latest/doc/technical/CreateCollectionProtocol.html

[ccnx repository] http://www.ccnx.org/releases/latest/doc/technical/RepoProtocol.html

[Jain91] - R. Jain, "The Art of Computer Systems Performance Analysis: Techniques for Experimental Design, Measurement, Simulation, and Modeling," Wiley- Interscience, New York, NY, April 1991, ISBN:0471503361.

[onl] Open Network Lab. http://www.onl.wustl.edu, 2011. http://www.onl.wustl.edu

[Wiseman08] Charlie Wiseman, Jonathan Turner, Michela Becchi, Patrick Crowley, John DeHart, Mart Haitjema, Shakir James, Fred Kuhns, Jing Lu, Jyoti Parwatikar, Ritun Patney, Michael Wilson, Ken Wong and David Zar.“A Remotely Accessible Network Processor-Based Router for Network Experimentation” In ''Proceedings of ANCS'', 11/2008. http://www.arl.wustl.edu/~wiseman/pubs/onl_sigcomm2009.pdf

[Eppstein11] David Eppstein, Michael T. Goodrich, Frank Uyeda, George Varghese, “What’s the Difference? Efficient Set Reconciliation without Prior Context” In ''Proceedings of SIGCOMM, 2011. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2018436.2018462

[Jacobson12] Van Jacobson, Rebecca L. Braynard, Tim Diebert, Priya Mahadevan, Marc Mosko, Nicholas H. Briggs,Simon Barber, Michael F. Plass, Ignacio Solis, and Ersin Uzun, Palo Alto Research Center, Byoung-Joon (BJ) Lee, Myeong-Wuk Jang, and Dojun Byun, Samsung Electronics Diana K. Smetters and James D. Thornton, Google Inc. “Custodian-Based Information Sharing”, in IEEE Communications Magazine 07/12, http://www.parc.com/content/attachments/custodian-based-information.pdf