| Ethan Shry, ethan.shry at wustl.edu (A paper written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) |

Download |

Current methods to manage networks are insufficient to keep up with the growing complexity of their infrastructure. Much of network management revolves around defining a protocol and managing device-specific policies and configurations, which makes it difficult for networks to scale efficiently, and fails to tie network policies to business goals. With the rise in virtualization and monitoring technology, Intent-Based Networking (IBN) has become possible. By defining intents instead of policies, and allowing an intent processor to interpret those intents into policies and configurations, network management is able to decouple itself from the specifics of the network infrastructure and traffic. This brings agility to the network management process and enables new avenues for network management. This paper aims to discuss key points in relation to the current state of IBN. It first covers the state of networking and how IBN aims to resolve issues in the traditional network management model. It then covers the technologies which make IBN possible and the process of where intents come from and how they are managed by the network. Finally, it discusses key challenges in the field and key pieces of work which have come out of IBN research and industry demand.

Keywords:Intent, Intent-Based Networking, IBN, Policy, Virtualization, Networking, NEMO, Orchestrator, Monitoring, Configuration, Management, Cisco DNA

As the level of complexity of corporate and consumer networks grows, so too does the complexity of network management. With the rise of the Internet of Things (IoT) and ever-increasing security concerns, network managers find themselves with an ever-growing list of devices to manage, and the current methods for network configuration fail to scale to meet these demands.

Recently, a variety of institutions have begun research into methods to increase the ability of network managers to effectively manage a multitude of devices, policies, and priorities, through the use of IBN.

This paper will explore the state of IBN. It will first discuss why current network management practices are lacking and how IBN will solve these issues. Then it will cover the major concepts of IBN implementation and the major points of contention in current IBN research. Finally, this paper will explore IB-Nemo and Cisco DNA, two of the most significant products spawned from the concepts of IBN research.

Current approaches to Network Management are not working. More and more devices and protocols are being added to networks every day, and the low-level device configuration approach to management is not scalable. By moving to intent-driven networking, network management can once again become scalable. Intents are high-level abstractions on policies, and allow network managers to abstract away protocol and device information, and instead focus on the end state of network traffic.

The time is ripe for a new approach to networking. The current demands on network managers are ever-increasing, from the number of devices to the number of protocols that need to be implemented. Security requirements and traffic priorities only increase in complexity, making traditional management practices more taxing than ever. At the same time, virtualization and real-time traffic monitoring have become much more prevalent in the modern networking stack, making a new approach much more feasible.

With the increasing prevalence of IoT, the total number of devices that are part of the global network is drastically increasing. Following current networking practices, network managers must exert significant effort to manage the policies impacting service to these devices. While in recent years, methods of managing these devices have become more automated, there are still a number of steps that must be completed under strict supervision. Additionally, network configuration and management still generally operates at a level too low to fully remove the need to tailor each solution to the specific device or protocol in use [Clemm19].

Additionally, the need for a vendor/platform-agnostic solution is more important than ever. More and more protocols are in use each year, and more and more companies have begun rolling out their own smart devices, which make use of unique methods of communication and traffic patterns. Moreover, the modern application still operates in the dark in regards to the network is relies upon. This means that the application can make no assumptions about the state or capabilities of the network, and vice versa [Elkhatib17].

Understanding the definition of intent is key to successfully understanding the power and role of IBN in modern networking. The intent is the highest level of abstraction from the hardware, and thus could be easily tied to a high-level business goal.

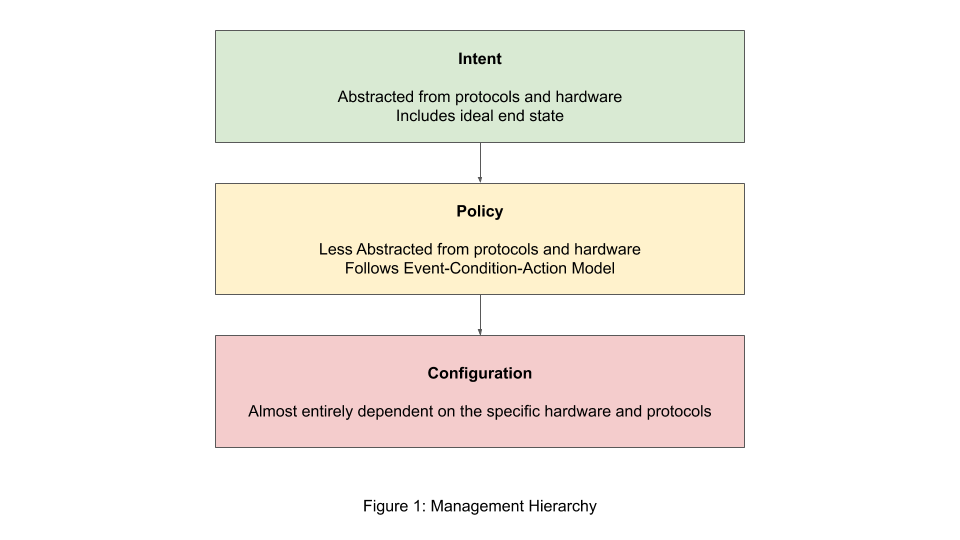

Figure 1 below shows the intent-policy-configuration hierarchy. In IBN terms, an intent is a high-level goal. The intent is ideally fully abstracted from any protocol, vendor, or even type of hardware. In practice, however, there is debate about the level of abstraction which is practical for real-world scenarios [Campanella19]. An intent is distinct from a policy or configuration in that intents contain a desired end state or result, whereas a policy or configuration only would specify an end action. Intents are composed of three main components- object, operation, and result. An object is a service, application, or resource which the intent is related to, operations specify exactly which actions should be governed by the intent, and the result specifies the end goal of the intent itself. For instance, an intent might be that a company wants its Skype (object) conference calls (operation) to guarantee HD video and high-fidelity audio to all participants (result). Intents are ultimately compiled into lower-level policies [Tsuzaki17].

Current networking is traditionally driven by policies or configurations. A policy typically is modeled with the event-condition-action model (i.e., on event, if condition, perform action). As a result, it is typically harder to tie a policy directly into a high-level network goal, and the reasoning behind a specific policy might not be immediately obvious. A policy will be less abstracted from the hardware or network protocols used, and might even be vendor-specific. Finally, a policy will typically be interpreted into a configuration. Configurations are highly protocol and vendor-specific and likely would not make any sense out of the context within which they are defined [Tsuzaki17].

IBN strives to remedy the shortcomings of traditional network management. IBN is a way to manage networks driven by intent, not via low-level configuration. To configure an intent-driven network, you would first specify a high-level goal (the intent). The network would interpret that goal into policies, and then deploy those policies across the network automatically. The network would be smart enough to be able to automatically deploy virtual devices as-needed, and resolve conflicts between intents within its domain.

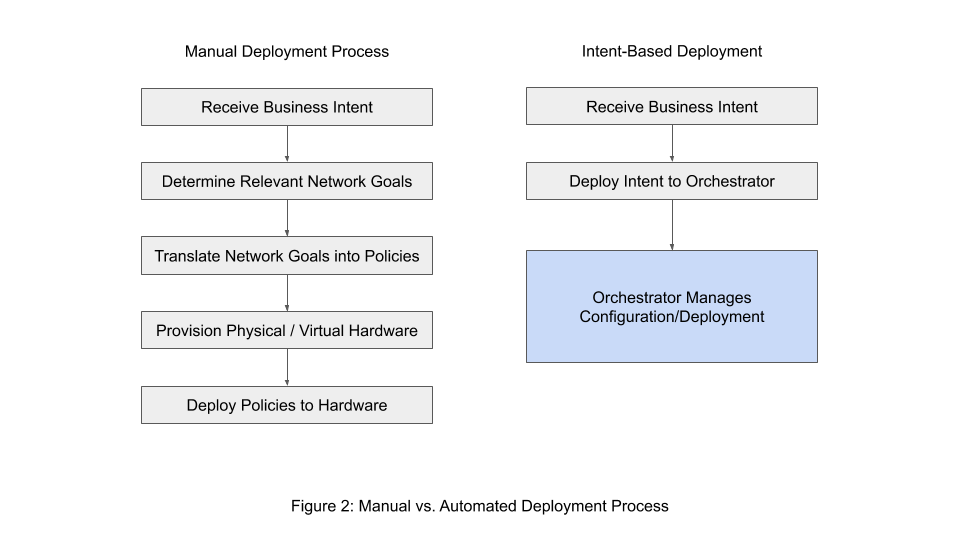

As a case study of the differences between IBN and traditional network deployment, imagine a typical business goal. Suppose executives want high-speed video conferencing to be the top priority within a corporate network (perhaps with a minimum resolution of 1080p). With traditional networking, network managers would need to translate that intent into a comprehensive set of policies (if there is video flow active and its resolution is lower than 1080p, and there is other traffic on this data line, halt the other traffic, etc.) These policies do not necessarily do a great job of capturing the end state of the intent behind their construction and are undoubtedly more prone to error (for instance, by failing to account for a potential edge case).

Additionally, the network manager must account for all the protocols and hardware which are used in this domain, since the presence or lack thereof of routers, or TCP vs. UDP traffic, might impact the policies needed to effectively capture the intent. With IBN, all of these choices would be offloaded to the intent orchestrator, and there would be no need to attempt to cover each possible scenario manually since the intent parser is able to effectively capture the entirety of the network capabilities, state, and intent within its auto-generated policies. Figure 2 shows the traditional network management order of operations, and the steps which are removed with a switch to IBN.

One major advantage of IBN is that it allows business goals to be tied directly to network configuration, instead of only being loosely tied together in a policy, as an intent also has an inherent outcome in mind (this concept is discussed more in-depth in Section 2.3). IBN also drastically reduces the amount of effort needed to deploy policies across a network. By tying policies to an intent, the need to manually deploy policies device-by-device goes away. Gartner estimates that IBN has the potential to reduce network configuration deployment times by up to 90% while cutting overall network outage time in half [Skorupa17].

There are several key requirements for an effective IBN, which have made practical implementation of the protocol difficult (or the value of its scope limited) until recently. Two of those features are the increasing prevalence of virtualization, in particular Network Function Virtualization, and the increased presence of telemetry and monitoring in corporate networks. Both of these tools are vital to get the most out of the IBN approach, and their widespread adoption is allowing IBN networks to begin to be used in a production environment.

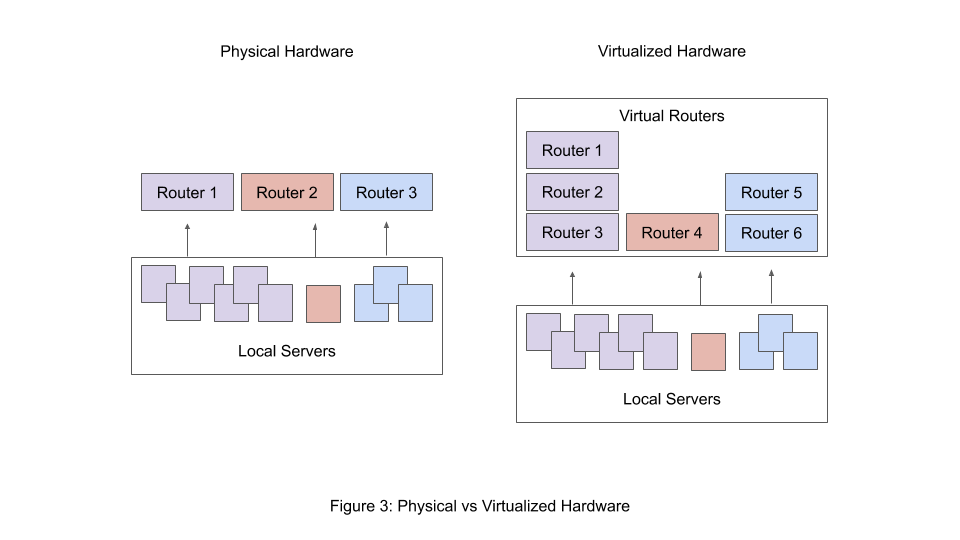

Virtualization, or the creation of virtual instances of a server, device, or function, has greatly improved the ability of IBNs to deliver improvements over a traditional network infrastructure. One of the key goals of IBN is flexibility. In a traditional network, you might have several servers, routers, bridges, or hubs. These devices might be from different vendors, have different capabilities, or have different protocols driving them. In order to integrate devices of this type into a network, network managers had to exert significant effort to set up the network infrastructure, ensure all devices can communicate with each other, and develop complex policies for network management. This meant that the addition of new hardware required re-working significant portions of the network, and many companies experience vendor lock-in as a result because there is a significant barrier to switching devices and protocols when the entire management and control plane is vendor-specific.

With Virtualization, all of this becomes much easier. By moving away from physical routers, bridges, and switches, and instead making use of Network Virtualized Functions (i.e. virtual routers, bridges, and switches), it is significantly easier to automate deployment of services. Should an intent require a device in a specific location, one can be created virtually instead of physically deployed [Subramanya16][Han16]. This makes the scope of policies that can be enacted significantly broader, leading to a more flexible IBN overall. Additionally, since devices are virtually deployed, they can be deployed under a tailored set of interaction protocols and a tailored set of capabilities, which removes the pain points of vendor-specific hardware.

Figure 3 demonstrates the benefits of Virtual hardware over physical hardware. Suppose we have applications talking over three distinct protocols. With physical routers, there need to be three separate devices to handle each type of traffic. These could be costly or time-consuming to acquire and configure, and even then, if traffic isn't evenly distributed across the three protocols the network might experience bottlenecks. With virtual hardware, there is only a need for a single physical device that automatically provisions as many virtual routers as necessary. Since the routers are virtual, it is easy to provision routers of the specific traffic type needed to achieve equal load across all three types of traffic.

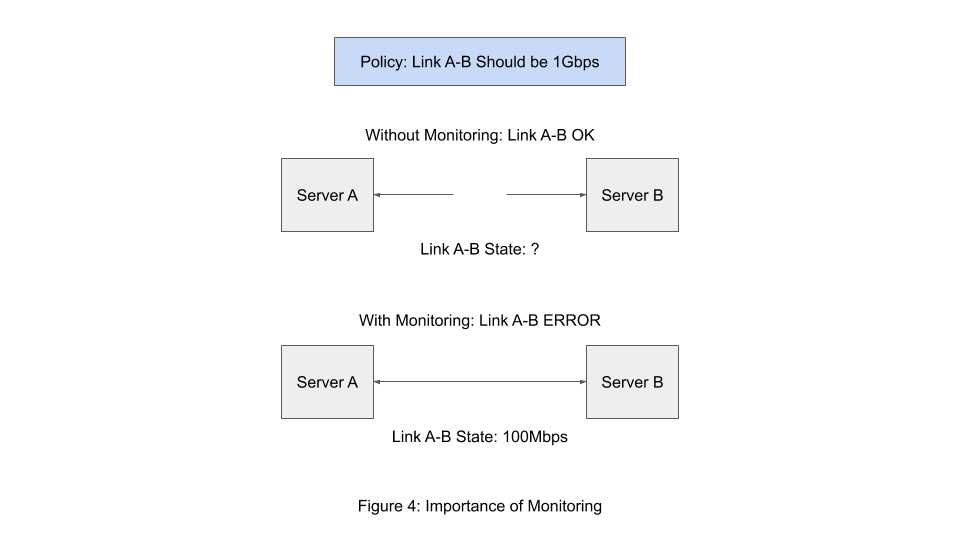

The second key requirement for an effective IBN is increased telemetry/monitoring presence. With the move away from policies and towards intents, there is a need to ensure the intent is effectively carried out. A policy following the traditional event condition action model has little need for monitoring, as there is no goal specified as a part of the policy. With an intent, the goal is explicit, and so monitoring of the network to ensure the success of that goal is critical.

Suppose an intent is defined by a network that all video conference streams are to be guaranteed 720p resolution and should experience infrequent interruption. Without monitoring video traffic of the organization, it is impossible to tell whether this intent has been successfully carried out. In fact, this monitoring needs to be highly specific, as not only must the network understand the quality of video streams entering and leaving the network, but it must understand their sources (i.e., Skype Business vs. Youtube), and perhaps their purpose (is the Skype call to a family member, or to a client). Additionally, when intents are layered (for instance, the business wants to guarantee high-speed download of files in addition to the above-mentioned video stream intent), it becomes clear that the only way to effectively enforce intent is to have high resolution, comprehensive monitoring in place across all aspects of the network. As is depicted in Figure 4, without monitoring it is impossible to communicate the true state of the network, which makes it impossible to effectively configure the network to ensure the highest quality of service.

The process of IBN management has four main stages: (1) Device Discovery, (2) Intent Delivery, (3) Intent Processing, and (4) Feedback & Monitoring. In Device Discovery, the network must understand the available set of resources it has access to. In Intent Delivery, network managers or Applications must deliver their intent specifications to the network orchestrator, which will interpret them for use on the network. In Intent Processing, intents are prioritized and broken down into policies that are used to define virtualized hardware and establish traffic rules. Finally, the network must monitor itself and ensure that the policies deployed actually satisfy the nature of the intents which define them in the Feedback & Monitoring stage.

The first step in an IBN is to understand the components of the network available to be used in intent delivery. While there is some contention (discussed in section 5.1), the generally accepted approach is that there is a single intent orchestrator that will handle the implementation of intents across a network. This orchestrator will live on a network, and when a device joins the network (or perhaps when the orchestrator requests device information for the purposes of implementing an intent) the devices must advertise themselves and their services to the intent orchestrator [Davoli18]. This period of advertisement allows the intent orchestrator the ability to understand the composition of the network, and makes it possible to smartly provision new services and organize existing devices as needed for the implementation of an intent.

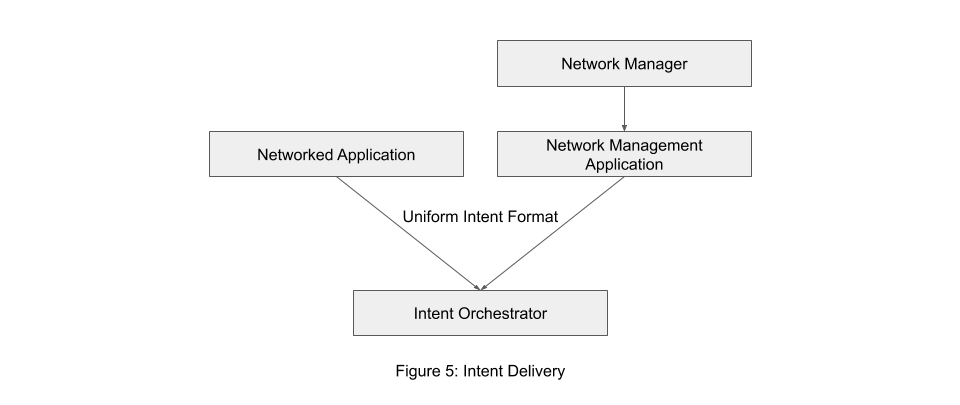

The question of intent delivery is twofold: determining who the source of the intent is and determining in what format an intent should be delivered to the Intent Orchestrator.

As is depicted in Figure 5, there are two primary sources for the intent. One of the main sources of intent is the network manager. When a business leader or network manager defines an intent, there must be a way for that intent to be specified to the network. There has not been significant effort put into determining how these intents should be delivered to the orchestrator since this is a relatively trivial task once there is an agreed-upon protocol in place.

The second potential source of intent is from an application. Much of the demand for IBN is as a result of the black box of the network from the application's perspective, and the black box of the application from the network's perspective [Elkhatib17]. Since the two do not understand each other's processes, they must expend unneeded effort in order to handle edge cases in each other. For instance, Youtube must implement logic to detect and handle poor network connectivity- this could be simplified if the application could simply specify to the network that it wants a best-effort high-speed video link. On the Network side, if the network understands that this application needs significant bandwidth for video traffic, it could set up a virtual high-speed data line when it sees Youtube, and a low-speed data line when it sees another application, as opposed to being essentially blind to the needs of an application.

Finally, there needs to be an agreed-upon standard protocol for intent delivery. There are a variety of proposed solutions, including various JSON representations. Augé discusses an addendum to the Yet Another Next Generation (YANG) data model, which would allow for the comprehensive expression of intent [Augé19]. However, the most prominent body of work is the IETF draft on an Intent-Based Network Modeling Language (known colloquially as IB-NEMO)[Hares15]. IB-NEMO is discussed in more depth in Section 5.1. IB-NEMO attempts to provide a modeling language covering 20% of intent options (which will serve 80% of network intents) as its preliminary goal. One of these configurations will need to be widely adopted by network devices in order to facilitate seamless communication across network devices for communicating intent.

There are two main stages to Intent Processing, (1) The breaking of intents down to policies and configurations, and (2) intent contention resolution. This section will discuss these two processes in detail, as well as the challenges associated with intent processing.

The first stage in intent processing is relatively straightforward to think about, but much more challenging to implement. Intents must be broken down into policies, which can then be broken down into configurations and deployed to devices. This presents several key challenges. First, the intent will require infrastructure to operate (for instance, an intent might require a number of physical or virtual routers, bridges, or switches). This infrastructure might already exist, or these resources must be spun up virtually. In either case, there are potentially multiple ways for the intent processor to implement an Intent, and so there must be some way to specify biases or understand which approach to resolving the intent is required. Furthermore, it is highly possible that resolving a specific intent is simply not possible, in which case there must be some feedback mechanism which will inform the requester of the status of their intent, and/or some lesser form of intent ought to be provided (perhaps in the form of best-effort service)[Sivakumar17].

Once an intent has been broken down into policies, contention resolution can begin. In the contention resolution stage, conflicting intents must be ranked, and arbitration between conflicting policies must be implemented. In some cases, it might be possible to recompile the intent into an alternative set of policies that do not conflict with an existing set of policies, however in other cases there must be some definition of importance or precedence which informs the intent processor which policies should have priority over others.

Once the set of intents have been transformed into non-conflicting policies for a network, the necessary network infrastructure can be spun up, and the policies can be deployed to their required devices. This stage must be repeated should the set of intents on the network change, or should the available resources change.

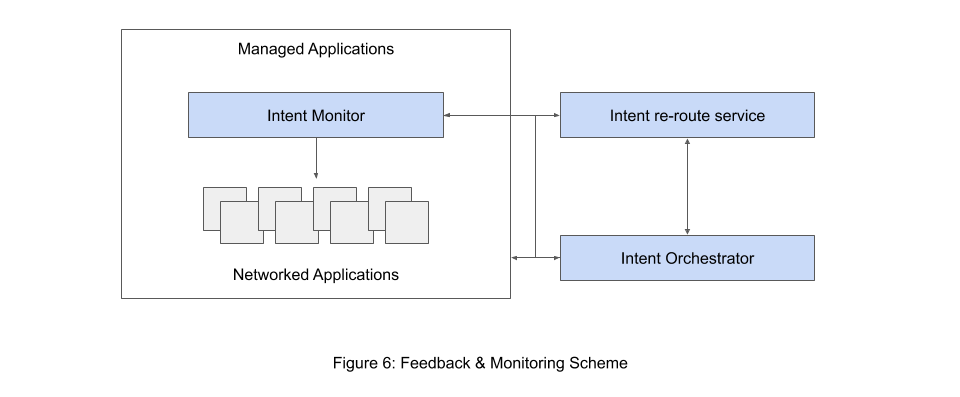

The final step of the implementation process is the Feedback & Monitoring stage. Once an intent has been processed into policies and configurations and deployed to devices, there must be monitoring of the network to ensure intents are successfully implemented. This involves ensuring all established links are maintained in an optimal state, and traffic is flowing as specified per the defined policies. Should the monitoring reveal a negative state (for instance, a device has become overloaded with traffic), the orchestrator must be informed and the network must adapt to the change in infrastructure [Sanvito18].

In some cases, this might mean recompiling the intent from scratch, or this might prompt optimization of the current network infrastructure by rerouting traffic based on the current network state, as is depicted in the figure below. By making use of rerouting logic the duration of the intent processing and contention period can be drastically reduced, making for a much easier fault recovery period. Figure 6 shows one proposed solution to the orchestration-monitor-reroute architecture [Sanvito18].

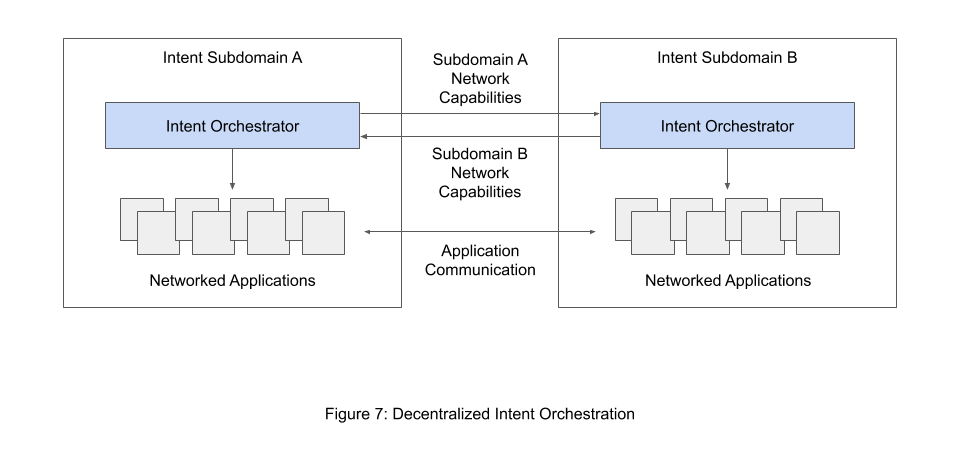

There are several key areas within the IBN space that present challenges to the practical implementation and effective use of an IBN. While most current research focuses on a centralized approach to intent orchestration, some argue that a decentralized approach is crucial to scalability of local networks. Additionally, in order to make full use of the IBN framework, understanding decentralized intent resolution is vital to the deployment of multi-domain intents. That being said, multi-domain intents introduce major security concerns, many of which have not been well researched to this point.

There is some debate within the IBN research space about the feasibility of using a single orchestrator for IBN network management. While it makes the network management much simpler to use a single orchestrator, some have proposed methods to allow for multi-node network orchestration.

The main issue with a single centralized network orchestrator is the amount of power required to maintain a large network. The centralized approach means that a single node has complete knowledge of the network, and has complete control over the flows and devices within it. This makes automation and intent deployment as straightforward as possible, but also means that the machine running the orchestrator has to have significant storage and processing power to maintain that level of information.

In a decentralized orchestration approach, the disparate orchestrators are able to maintain an incomplete picture of the network, which makes this approach much more scalable. That being said, it introduces challenges of its own- mainly, how can intent be processed efficiently across nodes with incomplete information. One proposed solution is to essentially break down a single intent network domain into smaller intent subdomains. As can be seen in Figure 7, each subdomain would have an orchestration node at its head, which advertises the capabilities of its portion of the greater intent network to each other intent network subdomain. This allows intent processors to understand the capabilities of the entire network, without actually needing to have a complete picture of the network infrastructure [Augé19].

Most of the work in the IBN space has revolved around single-domain intents, with a centralized orchestrator. As described in section 5.1 above, this raises issues with scale, but beyond that, a single-domain approach fails to account for significant use patterns of global traffic. In particular, a single-domain IBN ignores the potential conflict between a local intent and a provider intent, and doesn't take advantage of the potential value from a multi-domain network approach.

During intent contention resolution, the intent orchestrator arbitrates conflict between internal network policies. This is a complex process. However, since the orchestrator has complete control over the network, it is much simpler than an orchestrator attempting to perform the same process with an incomplete picture of the network. When multiple domains are in the picture, the contention process becomes much more complicated. The prioritization process which worked well on a local scale needs to now account for authority as well as priority (for instance, even if an application wants a 10G uplink to an external server, if the network owner hasn't paid the provider for 10G uplink service, they don't have the authority to provision such a service). Additionally, the issues of incomplete information in a decentralized IBN discussed in Section 5.1 come into play. That being said, Arezoumand et al. have done work into developing a proof-of-concept Local / Global IBN, which attempts to resolve these issues and provides an outline for what a Multi-Domain IBN would look like [Arezoumand17].

When an IBN can express intent across multiple domains, the possibilities of intents grow exponentially. Intents that might not be feasible at the local level could become feasible, and there are new avenues for useful intents. When an intent has the ability to span all servers across the globe, the avenues for optimization and security are endless. Imagine a firewall which operates on the sender, as opposed to the receiver, preventing spam email from being sent before it leaves the sender's local domain, instead of blocked on the receiving end, or an intent which ensures that government data travels only through network infrastructure of a country which is allied with the source country, improving overall data security.

The development of IBN leads to a variety of security concerns. In particular, when an application is in charge of requesting services instead of a network manager, the question of authority comes into play. Additionally, when an intent orchestrator has a role in setting up optimized, secure pipelines, and is potentially in control of which protocols to use, the question of security is also raised.

As discussed in Section 5.2, in a multi-domain network, the question of whether an application has a right to ask for a specific intent is raised (though this is also possible at the local domain level, it is most easily illustrated in a multi-domain scenario) [Arezoumand17]. In these scenarios, it is important that the idea of ownership plays a role in intent contention resolution. For instance, an application that requests a service of the network provider likely has less authority than the provider itself in terms of which intent ought to be satisfied. Similarly, a local domain probably ought to have more say in the traffic which passes through it than the authority of intents specified by an external domain.

Additionally, there is the issue of secure flow provisioning. In the intent-policy-configuration translation process, the orchestrator will likely need to make decisions about which type of security makes sense for a specific application. For example, a specific flow that needs to be both fast and secure has the option of physical layer encryption or layer 3 encryption. These methods both have tradeoffs, and so there is a need in the IBN space for researchers to look into these decisions and propose ways orchestrators or applications should help arbitrate contention or specify security requirements [Szyrkowiec18].

There have been several significant pieces of work that are impacting the adoption and research into IBN. IB-NEMO is in the draft stage at the IETF and is seeking to provide a minimally viable language for modeling network intent. Cisco, whose employees have authored many of the references used by this paper, is also working on a digital networking platform that seeks to make use of concepts spawned by IBN to deliver value to businesses across the globe.

IB-NEMO is designed as a way for applications to communicate their intents to an intent orchestrator. It aims to serve as a minimally viable protocol and believes that by implementing 20% of the most commonly used intents, it can satisfy 80% of the actual intents desired by applications.

IB-NEMO is specifically looking to satisfy a few different use cases. These are highlighted in its IETF draft, including Virtual WAN, Virtual Data Center, Bandwidth on Demand, and Service Chaining. By implementing these key areas, IB-NEMO covers a variety of intent topic areas. These areas require IB-NEMO to be able to deploy virtualized devices (routers, bridges, etc), as well as Network Virtualized Functions like load balancers and Firewalls. Additionally, IB-NEMO seeks to be able to comprehend a variety of generic intent concepts, such as time and protocol.

IB-NEMO has progressed through the first three stages of its design goals (revolving mostly around proof-of-concept). At this point, it is focusing on ensuring the subset of intents it is designing for is useful to applications, the syntax is logical and clear, and to get as many developers and device manufacturers on board as possible [Hares15].

Cisco, as one of the leaders in the commercial networking space, is working on an intent-based platform for network management. Coined Cisco Digital Network Architecture (Cisco DNA), Cisco has developed a suite of solutions that fall in the general realm of IBN. They have a suite of tools to automate network management, ensure security compliance, guarantee network performance, and ensure network access [Cisco19].

In particular, Cisco DNA provides for policy-based device onboarding and management, which is continually becoming smarter and is trending towards intent-based management. Their network monitoring and analytics platforms are allowing network managers to begin to leverage telemetry data in the monitoring of the network, and by providing context to policies within the DNA platform, Cisco is beginning to set up the building blocks for a commercial IBN [Cisco19].

Traditional Network Management is unable to keep up with the increasing demands of ever-growing network infrastructure. Powered thought the rise in monitoring and virtualization, networks will soon be able to be intent-driven. By moving to a model where intents are used to manage networks, instead of protocol and hardware-dependent policies, network managers will be able to have more effective controls over the network, and will be able to tie network policies directly to business goals.

Intent-driven networks typically have a single orchestrator, which understands the capabilities of the network it owns, processes incoming intents into policies, resolves conflicting intents on the network, and delivers those intents to the devices it manages. It then must monitor the state of its network to ensure the policies enacted are satisfying the intent of the applications which drive network requirements.

There are several key issues in the field which are under development, including ways to move from a centralized to a decentralized approach to intent orchestration, and ways to resolve intents across orchestration domains. At the same time, there have been a few areas that have been well-developed, such as the IB-NEMO modeling language, and Cisco even has key components of intent-driven networks in commercial use as part of its DNA platform.

| DNA | Digital Network Architecture |

| HD | High Definition |

| IBN | Intent-Based Networking |

| IETF | Internet Engineering Task Force |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| JSON | Javascript Object Notation |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| WAN | Wide Area Network |

| YANG | Yet Another Next Generation |