| Brendan Yang,b.z.yang@wustl.edu (A paper written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) |

Download |

Low-Earth Orbit Satellites, Internet of Things, constellation topologies, wireless, 6g, Direct-to-Satellite

The development of low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites has brought many innovative technologies into the realm of networking and communications connectivity. Wireless devices that users, communities, and entire countries possess, now have the potential to be reached by orbit to provide universal Internet access to devices anywhere. This opens a new realm of technological computing power readily available for use by many Internet of Things devices.

Although many modern efforts like Starlink, Telesat, and 6G applications aim to provide users connectivity, the world of IoT devices reigns supreme in the count and in their necessity to remain constantly connected to provide network resources and process endless streams of traffic. This resulting paper provides an analysis of LEO satellite-enabled IoT networks, their architecture and applications, and ultimately a conclusion to deliberate on future developments and considerations to be taken on the technology.

Several technologies must be put into place to enable LEO satellite networks and permit efficient communication to and throughout the network and are commonly regarded as the standards for satellite networks.

Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites are spacecraft placed into orbit around the Earth at an altitude of approximately 500 to 2000 km, allowing the satellite to complete an entire orbit in less than 2 hours [Wang07]. LEO satellites are preferred for user-access applications given their relative proximity to the surface, as opposed to medium-Earth orbit (MEO) and high-Earth orbit (HEO) satellite groups. LEO satellites provide lower latency in data transmission and are less expensive to reach their target altitude. The periodicity of their orbits also enables more reliable and consistent coverage of a specific area by being able to perform multiple flybys in a shorter time.

For LEO satellite networks to be practical in today's IoT ecosystems and their rapidly growing demands, the satellite network must be capable of achieving wide-coverage, high-bandwidth communication among the satellites themselves. The distance between satellites can range over many hundreds of kilometers in each satellite shell, within a region of the network known as the “space segment”. To overcome the difficult nature of the space segment, much research and development is put towards efficient inter-satellite links (ISL) that provide mesh-topology connectivity between satellites within the network. The ISLs operate over various frequency bands that can include the Ku and Ka-band radio communication frequencies. Several examples of such ISLs are in place within Telesat communications that operate on the V-band for a latency of 30 to 50 ms, and the well-known Starlink system operates with a latency of 25 to 35 ms [Yongtao19]. Without such ISLs, the latency of satellite networks would render the use cases of such a network to very few applications or require an exorbitant number of satellites to achieve the same effect.

Inter-network communication is not the only concern when designing these satellite networks. Making sure that the uplink and downlink of the network between the surface can withstand the amount of traffic that IoT devices generate is also crucial. Similarly, to how ISLs operate, there are ground gateways in place on the surface that act as connectivity points for surface networks. These are connected to the satellite network through “feeder links” that permit direct communication with the LEO satellites. Throughout the ground segment exists a multitude of protocols to communicate with the satellites, such as radio-link control (RLC) protocols and network management centers (NMC) to act as base stations for the user segment of the network.

These NMCs typically consist of hardware including antenna arrays capable of beamforming, broadband processing units, and network interface entities [Su19]. Important tasks of the NMC are generally the operation and control of satellite communications, carrying out radio resource scheduling between multiple end-users, as well as satisfying QoS constraints as outlined within SLAs. These actions must be all carried out before finally providing connectivity between the satellite network and the Internet or network of IoT devices.

Fig. 1 - Block diagram illustrating connectivity between various segments of the network, the left illustrating user-end features with the right depicting the ground segment block diagram.

Credit: Su19

Various methods of physically creating the link between the space and ground segment exist through the application of different satellite beam coverages. Beams describe the radiation pattern generated by the electromagnetic wave used to transmit traffic between antennas. Satellite beam coverage typically comes in the form of spot beams and hybrid wide-spot beams. Spot beams are widely applied in LEO systems due to the number of satellites that are present above a region at a time. Through this, multiple spot beams per satellite can be achieved along with dynamic beam-steering to arrange beams in various patterns to achieve high-bandwidth communication. For example, the Iridium satellite constellation system uses 48 beams per satellite for cellular coverage of the Earth and the OneWeb internet system has each satellite generate 16 elliptical full beams in-line [Liang22]. The specific pattern generated by these beams directly influences their capability in various environmental conditions, where spot beams generally provide the most directed and therefore highest gain in their signal but narrowest in its footprint on the region serviced.

Regardless of the advantages that LEO satellites provide for connectivity, the network is useless if it does not contain enough satellite points. Every satellite network must be composed of a multitude of satellites and efficiently structured into a constellation of various planes to provide adequate connectivity to the surface, as well as enabling bandwidth for ISL traffic. A single plane of the network is typically visualized as satellites following a trajectory that orbits parallel along the longitude lines while neighboring planes are separated by an angular distance along the latitude lines. The constellation is then often described as a N×M matrix of N planes within a constellation with M satellites per plane.

The Polar constellation sports N planes separated at 180 degrees divided by the N planes with an orbital path that is near-polar such that the satellites perform flybys across the North and South poles. As a result, neighboring satellites are easily accessible between adjacent planes as satellites move regularly toward the poles. The construction of this network is simple; however, it does come with its limitations.

The first difficulty is the convergence of satellites at the poles of the Earth, which results in a large overlap between satellite ISLs and noise interference. This can be typically solved through dynamic switching of activity when satellites reach the poles, but it is not ideal. In addition, within this type of constellation, there exist “side seams” where neighboring (same altitude) planes are co-rotating in opposite directions [Junfeng07]. This results in a large amount of ISL handoffs as the satellites at the edge of the planes constantly fly by each other. Such an issue is eliminated in the Walker Delta constellation.

In the Walker Delta (or simply Walker) constellation, the N planes of the network are separated with a constant angular distance of 360 degrees divided by N planes to create a mesh that appears to have each satellite equidistant at its equatorial region. The Walker constellation provides much better dispersion of satellites across the globe with fewer overlaps at the poles, as well as eliminating the existence of side seams by ensuring all satellites rotate in the same direction (which is permitted by the angled orbital pattern of each plane). The greatest downside of this constellation is that in general long-term, stable ISL links are difficult to establish due to the constantly changing relative heading between satellites in adjacent planes.

Fig. 2 - Illustration of Walker Delta (a) orbital pattern versus a Polar (b) pattern

Credit: Su19

Naturally, a network being positioned so distant from the surface and widely dispersed over many kilometers of space that may be obstructed due to environmental factors (like weather and geography) poses many physical networking difficulties. Power requirements and path loss are only a few of the many major issues that must be overcome in a satellite network.

To support high-traffic data that may arise from the connection of many IoT devices to the network, as well as providing broadband connectivity to such devices, an interesting protocol of inter-satellite communications is investigated. The Satellite-over-Satellite (SOS) network consists of multiple layered satellite constellations formed by both LEO and MEO satellites to address the difficulties that arise from sparser networks comprising long distance-dependent (LDD) traffic [Lee00].

The primary issue with typical constellation architectures involves the use of only a single layer of LEO satellites, where when the network is sparse there exist long latency costs between traffic hops. To optimize this, SOS analyzes the bottlenecks in traditional networks, namely the number of traffic hops, resource allocation via a hierarchical QoS routing protocol, and optimal path selections. The hierarchy of SOS is divided into both physical and logical groups, with physical groups of LEO satellites serving as the edge link between user space for near-distance traffic with lower-power IoT devices. The MEO satellites are connected to the LEO group via inter-orbit links (IOL) to elevate traffic into a more sparse but wider-coverage MEO layer to reduce the number of hops. The logical grouping of LEO satellites involves a tree-like structure of n layers, where several groups of satellite nodes within layer 1 cluster together with a designated satellite acting as a node in layer 2, and layer 2 nodes clustering to form each sequential node up to layer n. The reason for this is to better organize the number of satellites that cross-traffic communicates between and provide a tree-like structure to determine the optimal routing path via a hierarchical routing protocol to meet QoS priorities.

Traditional methods of radio communication frequencies are often capable up to a certain extent until maximum physical bandwidth limits are reached due to the frequency of the electromagnetic wave that carries encoded information. Typical RF frequencies range between the MHz to GHz ranges, but laser frequencies that operate within infrared spectrums can achieve up to THz levels. With over 100 times the frequency, optical laser arrays are becoming the next novel method of enabling blazingly fast communication between satellites, similar to how optic fiber brought much higher levels of bandwidth as opposed to copper.

Such a concept is not without its difficulties, the primary ones being that lasers are by nature completely directed and suffer from significant loss and noise if their line of sight (LoS) is impeded by rain fade, clouds, and other geographical obstacles (namely atmospheric bouncing of signals is no longer possible as with traditional radio frequencies). However, technologies are being investigated capable of dynamically directing laser arrays complete with target acquisition and tracking to reliably control such sensitive devices. The device consists of small, compact lenses with a photodetector array to create a self-contained system controlled by gimbals and steering mirrors [Goorjian19]. In the context of an LEO network, such communication becomes much more feasible where satellites are typically adjacent without any atmospheric obstructions. Although the technology will likely not be used for servicing the link between space and ground segments of the network, its usefulness within the space segment is certain to improve the latencies associated with LDD nodes within a constellation.

In addition to space segment architectures, the actual communication between the satellite network is also important, where two technologies have recently been proposed for improving the power-constrained environment that small IoT devices typically operate under.

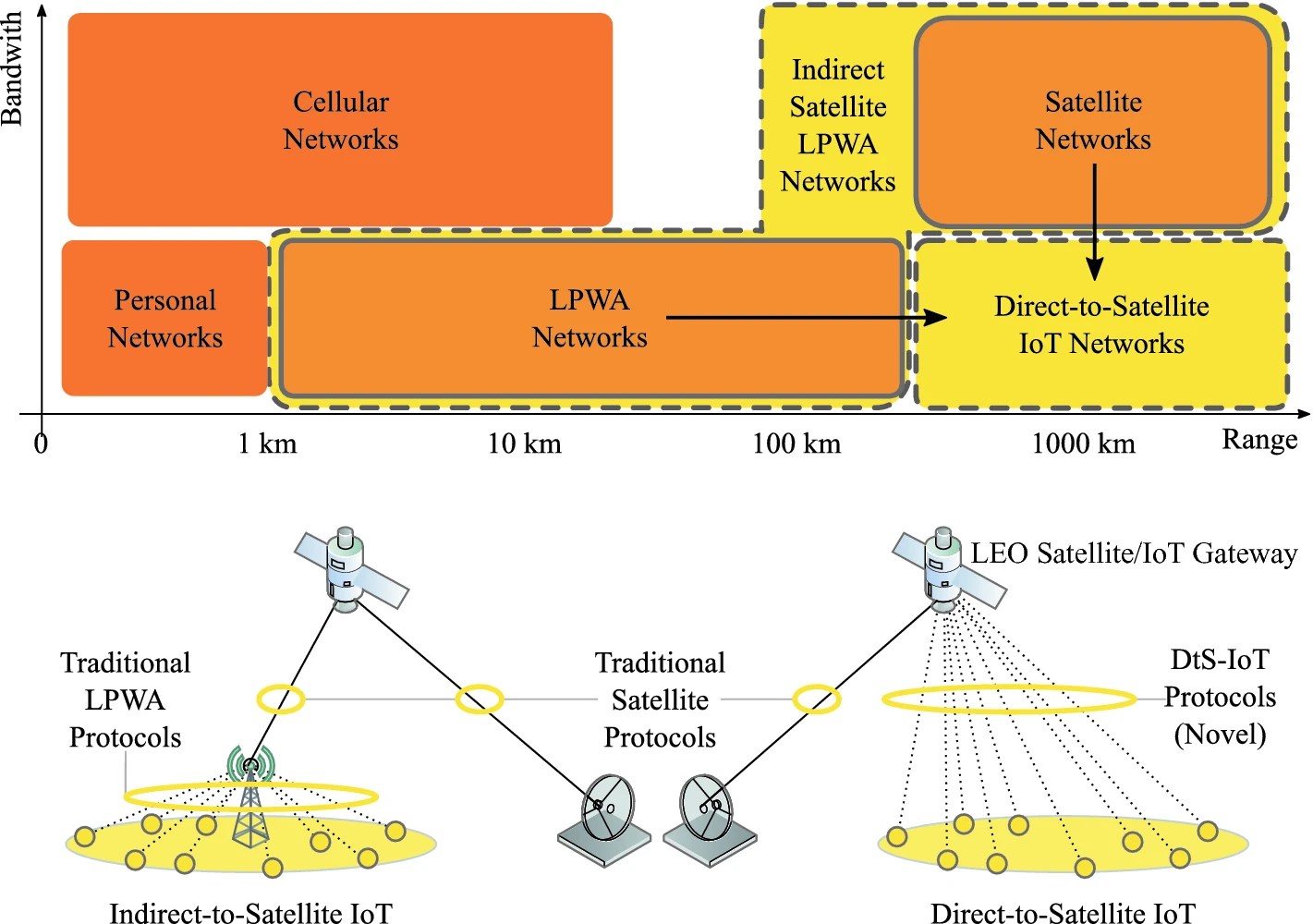

Low-power Wide Area Networks (LPWAN) are the traditional networks used by large networks of IoT devices that must communicate between themselves and a gateway to access further distance networks. The design of LPWANs advocates for the use of gateways that act as central communication links for IoT devices that can only communicate on lower power transmissions, and therefore shorter ranges. To enable WAN coverage, however, the gateways are installed with additional hardware and infrastructure that allow it to communicate with greater transmit power.

The obvious downside of such a ground segment network is that infrastructure must exist for IoT devices to operate within a region, as well as the fact that the IoT devices themselves are constrained based on their distance relative to the gateway.

Direct communication between a ground segment device and a satellite typically is well suited for environments where gateway infrastructure is lacking, whether due to geographical difficulties in setting up prior logistics or when preexisting infrastructure is temporarily out of service. As such, protocols that define Direct-to-Satellite (DtS) communication become of great interest for its flexibility and rapid ability to be deployed at a time.

Fig. 3 - Block diagram illustrating the comparison of DtS IoT communications (bottom right) access methods as compared to traditional LPWAN and satellite protocols.

Credit: Fraire19

Two protocols for enabling such capabilities have been on the rise, namely Narrow-band IoT (NB-IoT) and Long-Range (LoRa) modulation schemes. The primary reason is their energy-efficient schemas for modulating information on the frequency spectrum. NB-IoT operates on the 3G/4G frequency spectrum, while LoRa communicates on a 900 MHz unlicensed band. To save on energy costs, LoRa makes use of a “spread spectrum” modulation method, where the original signal is spread onto a wider bandwidth through frequent low-power “chirps” whose patterns of instantaneous changes in frequency are instead used to encode information. NB-IoT focuses on optimizing the number of bytes required to be transmitted over the air and thus settles for a short fraction of the frequency spectrum, which provides it with natural noise and interference resistance [Fraire19]. The communication of the IoT devices with the LEO satellite nodes is often then achieved through random access protocols, such as Slotted Aloha and Contention Resolution Diversity Slotted Aloha due to the relatively infrequent pings that the IoT devices would be making in the remote environment that the sparse network operates.

Although the presence of an unlicensed band can pose significant interference problems, DtS communication aims to service areas of underpopulated regions and thus still has reasonable applications in those areas.

As with all IoT computing devices, limited resources, and low-power constraints are all requirements that these devices must overcome. This becomes especially apparent when satellites aim to provide ubiquitous coverage for IoT devices that have limited battery capacity despite the long-range transmission that must occur over DtS links. As such, the research of reconfigurable intelligent surface (RIS) units is being conducted for satellite antenna arrays to provide dynamic broadcast and beamforming control that ultimately increases the gain of signals received and transmitted by the IoT device and satellite.

Such technology is implemented through meta-surfaces that are controlled electrically to perform real-time adjustment of reflective communication arrays during the reflection phases of transmissions [Tekbiyik21]. Numerous amounts of RIS units would be installed underneath satellites' solar arrays whose large surface area permits these small form-factor devices. Multiple RIS units are then capable of beamforming to selective target users on the surface, mitigating losses due to path loss from rain attenuation and other atmospheric conditions. Any improvement in the link between a DtS link will ultimately result in saving the IoT device on power costs, where less power is required on the IoT device's end when the satellite increases the gain of the link signal.

Green data collection methodologies have also been proposed on the IoT device application side, where determining the frequency and specific time at which IoT devices communicate and establish communications between the satellite network is optimized. This is achieved through a novel online algorithm for “green-data” uploading, where the time-varying uplinks are analyzed based on atmospheric conditions, orbital schedules of overhead LEO networks, and developing a scheduler based on those factors [Huang19]. The algorithm operates on various discrete time slots with ranges between milliseconds to seconds, where the known positions/schedule of the satellite planes are used to determine the likelihood of when an IoT device’s queue of backlogged data should be uplinked.

Access between the green-data IoT devices and satellite networks are done through an LPWAN access gateway, of which multiple connections are distributed over all three OFDM, FDMA, and TDMA hybrid multiplexing mechanism. When an uplink is requested, the gateway assigns the IoT device a unique channel following one of those schemes based on the satellite's data-receiving capacity. For example, TDMA channels would be used for satellites that can communicate on higher frequencies where the transmission bandwidth is relatively high and thus takes less time to fully upload a device’s backlog to the LEO network.

A last topic of application that LEO satellites have recently been a trending candidate for is the creation of a 6G wireless network. This is especially important for IoT devices that rely on high-bandwidth, wide-area wireless communication. The primary goal of evolving 5G to 6G involves providing limitless connectivity everywhere, including remote and terrestrially complex regions that are traditionally difficult for traditional wireless infrastructure to reach.

The ability for mega-constellation LEO networks to provide this capability requires that the satellites be relatively low, around 600 km for a design proposing a large wave of satellites (on the order of thousands) to communicate with cellular towers across the surface of the Earth [Lin21]. This faces several challenges with the scale of a mega-constellation, namely cost and the need to develop cheaper satellite vehicles that operate more efficiently. This is addressed through the fact that 6G will typically not cover ocean bodies and thus the satellite can be effectively switched off when not over land. The common shared access mechanism proposed is the use of OFDM to support a wide range of subcarrier traffic. However, the physics of satellite orbits introduces noise due to phenomena like the Doppler effect which requires shifting of signal frequency based on the velocity of the satellite body and heading of transmission beam.

Upon overcoming these obstacles though, the potential for 6G connectivity over LEO satellites would provide revolutionary connectivity across the globe at an unprecedented scale. Internet access over 6G would enable many smart IoT devices to perform computing truly anywhere on the surface.

LEO satellites, given the proximity to the Earth's surface, offer many benefits such as reduced latency and cost-effectiveness, making them the next trending choice for delivering widespread Internet access as well as addressing the connectivity needs of constrained IoT devices. The advancements that will only continue to come from the rapidly developing space infrastructure being put into place by many companies will only serve to further develop LEO satellite networks capable of interfacing with IoT devices. The creation of these networks holds great promise for revolutionizing the networking landscape that IoT devices have traditionally operated within, enabling end-users and businesses to perform device computing anywhere on the globe at a completely new level. Research like this is crucial for addressing the challenges that will inevitably come with the integration of satellite communication with our IoT ecosystem if progress is to be made towards evolving the current state of IoT devices. The rapid growth of LEO satellite networks truly underscores the importance of this continued research now and into the future.

Y. Su, Y. Liu, Y. Zhou, J. Yuan, H. Cao and J. Shi, "Broadband LEO Satellite Communications: Architectures and Key Technologies", 2019, pp. 55-61, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8700141

Zhichen Qu, Genxin Zhang, Haoton Cao, Jidong Xie, “LEO Satellite Constellation for Internet of Things”, 2022, pp. 18391-18401, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8002583

L. Jin, L. Wang, X. Jin, J. Zhu, K. Duan, and Z. Li, "Research on the Application of LEO Satellite in IOT," 2022, pp. 739-741, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9832117

Junfeng Wang, Lei Li, Mingtian Zhou, “Topological dynamics characterization for LEO satellite networks” 2007, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2006.04.010

Jaeook Lee, Sun Kang, "Satellite over satellite (SOS) network: a novel architecture for satellite network", 2000, pp. 315-321, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/832201

Peter Goorjian, “Free-Space Optical Communication for Spacecraft and Satellites, including CubeSats in Low Earth Orbit (LEO)”, 2019, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20190028633/downloads/20190028633.pdf

Gabriel Maiolini Capez; Santiago Henn; Juan A. Fraire; Roberto Garello, “Sparse Satellite Constellation Design for Global and Regional Direct-to-Satellite IoT Services”, 2022, pp. 3786-3801, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9806168

Juan Fraire, Sandra Cespedes, Nicola Accettura, “Direct-To-Satellite IoT - A Survey of the State of the Art and Future Research Perspectives” 2019, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-31831-4_17

K. Tekbıyık, G. K. Kurt and H. Yanikomeroglu, "Energy-Efficient RIS-Assisted Satellites for IoT Networks", 2022, pp. 14891-14899, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9539541

H. Huang, S. Guo, W. Liang, K. Wang, and A. Y. Zomaya, "Green Data-Collection From Geo-Distributed IoT Networks Through Low-Earth-Orbit Satellites", 2019, pp. 806-816, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8681409

X. Lin, S. Cioni, G. Charbit, N. Chuberre, S. Hellsten and J. -F. Boutillon, "On the Path to 6G: Embracing the Next Wave of Low Earth Orbit Satellite Access", 2021, pp. 36-42, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9681631