Security of Autonomous Vehicles

Abstract:

As autonomous cars begin to disrupt the automobile industry, concerns about the security of these cars remain large. Already many modern cars offer features which essentially drive or park the car automatically. For the first time, miniature computers within the car have the ability to physically control the car. This paper examines recent research into what is possible when plugged into a car’s internal network as well as how attackers could remotely gain access to a car. This paper is not meant to be worrying, but instead is meant to draw attention to the attack surface and begin working towards a more secure system.

Keywords:

Security, Autonomous Vehicles, ECU, CAN, OBD-II, Bluetooth, PassThru

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

More and more cars offer a range of driving assistance features from auto parking to staying within the lanes on the highway. Many people believe that self-driving cars are the future. Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors, believes that by “next year [Tesla cars] will probably be 90 percent capable of autopilot” [Moyer14]. This confidence in the technology makes autonomous cars seem quite near in the future. The question remains, how safe are these modern day cars and could they be attacked or compromised?

Traditionally, vehicles ran on hydraulics and mechanics. In the 1980’s, Intel and Ford teamed up to develop the Electronic Engine Control which has transformed into the Electronic Control Units (ECUs) of today. As car manufacturers offer more and more features, the car requires more ECUs to control sensors and process the data. Even more recently, the features in Figure 1 such as Automatic Braking, Lane Correction, and especially self-driving capabilities can manipulate acceleration, braking, and steering [Braga14].

Additionally, with the introduction of autonomous cars there will be advanced sensors such as the Light Detection and Ranging system (LIDAR), wheel encoders, infrared camera, etc [Vanderbilt12]. These sensors also rely on ECUs to process the information and make rapid decisions. This paper examines what is possible if malicious attackers have access to the car’s internal network, how they can remotely attack a car, and how the industry should move forward as autonomous cars become more and more of a reality.

Additionally, with the introduction of autonomous cars there will be advanced sensors such as the Light Detection and Ranging system (LIDAR), wheel encoders, infrared camera, etc [Vanderbilt12]. These sensors also rely on ECUs to process the information and make rapid decisions. This paper examines what is possible if malicious attackers have access to the car’s internal network, how they can remotely attack a car, and how the industry should move forward as autonomous cars become more and more of a reality.

1.1 How it works

Today’s modern vehicles already differ from traditional mechanical automobiles because the cars of today may contain 50 or more ECUs networked together to provide these additional features [Miller14]. Each ECU can be thought of as a miniature computer with a specific task. These ECUs work together on one or multiple buses which are based on the Controller Area Network (CAN) standard. Vehicles rely on communications between these ECUs, and as a result, these networks of ECUs are extremely important.

The CAN standard has been designed for rapid transmittal and continuous processing of information. To start, CAN packets are broadcast to all ECUs on a bus. This design decision allows all components to be able to access critical information quickly, but in terms of security, broadcasting allows attackers to monitor and even send traffic over the CAN network. However, an inadvertent benefit from broadcasting is the decentralized nature of decision making. For example, each individual ECU processes the CAN packet differently and uses the data differently [Miller14]. It requires a lot of effort to reverse engineer which CAN packets matter and which ones do not.

2. Control Area Network attacks

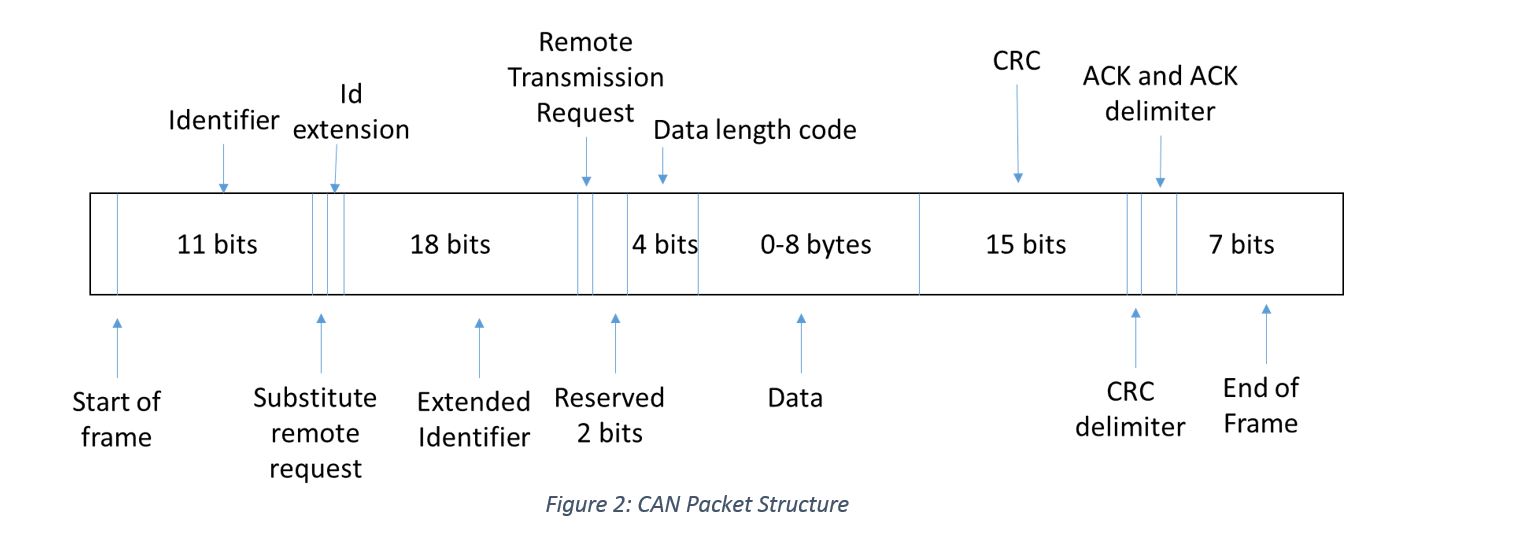

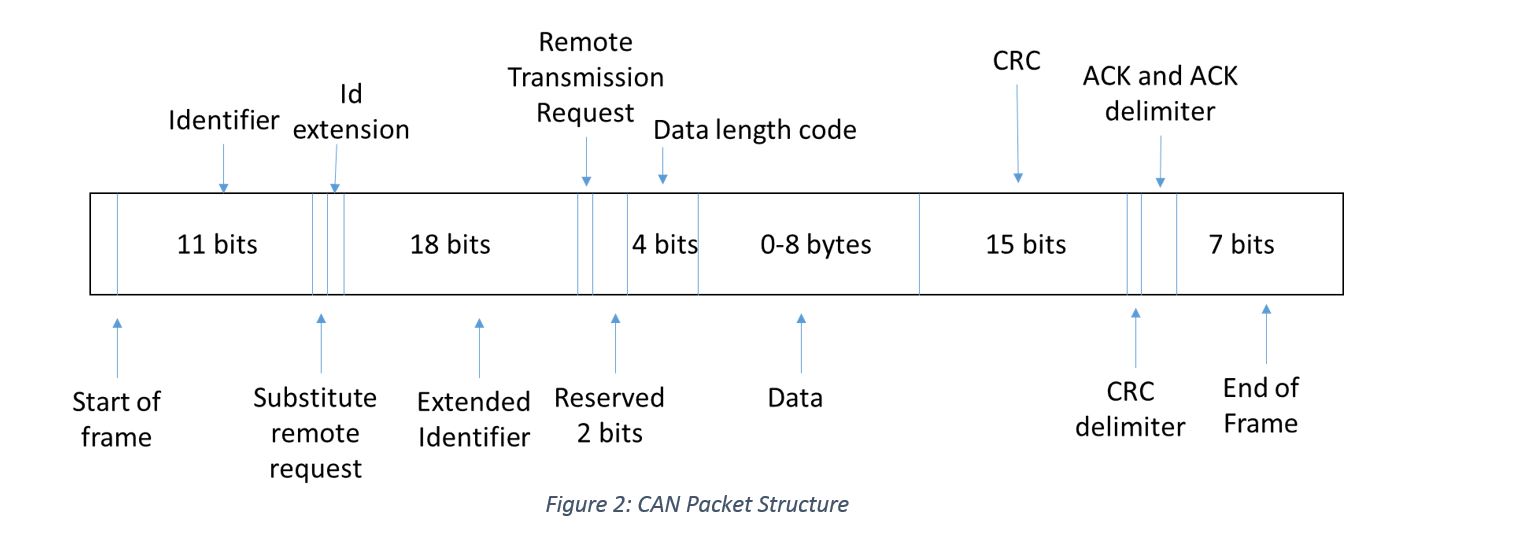

As a result from the low latency environment, CAN networks have to prioritize certain packets. As seen in Figure 2, each CAN packet contains an identifier and some data. Identifiers can be either 11 or 29 bits and are followed by 0 to 8 bytes of data. By design, CAN packets with lower identifiers receive higher priority than packets with higher identifiers. As a result, attackers can flood a network with CAN packets with an identifier of 0 which will have higher priority than any other packet. ECUs will react to a Denial of Service (DoS) attack differently. One research study found that the “Power Steering Control Module (PSCM) ECU completely shut down” which causes it to “no longer provide assistance when steering” [Miller14]. For the same car, if an attacker spams CAN packets “before the car is started, the automobile will not start” [Miller14]. By design, the CAN standard is vulnerable to certain manipulations from the outside.

While car design differs depending on manufacturer, with enough effort, attackers can generally accomplish the same goal on all cars. These attacks vary in magnitude and in danger to the victim, but it is clear that malicious entities can completely manipulate the cars against the wills of the driver.

2.1 Radio

Researchers were able to manipulate the radio volume and prevent the user from lowering it. In addition, attackers can reproduce the various clicking and chimes (turn signal, open door chime, etc.). While this attack is not inherently dangerous, it can be extremely frustrating to the user [Greenberg13].

2.2 Instrument Panel

Researchers have been able to completely control the Instrument Panel Cluster of the car. Having such control allows the attacker to “display arbitrary messages, falsify the fuel level, speedometer reading, adjust the illumination of instruments”, and more [Koscher10].

2.3 Body Controller

The body controller modules (BCMs) control much of the user interactions with the car. Attackers have been able to find the CAN packets that are sent to the BCMs to “lock and unlock the doors; jam the door locks; pop the trunk; honk the horn;” and much more [Koscher10]. In order to influence the BCMs they would have to be unlocked with a control key, an additional step that attackers would have to bypass.

2.4 Engine

Researchers were able to disable power steering, temporarily increase the RPM, and completely kill the engine of the car. They were able to reproduce these “at speed” – while the car was jacked up on a stand and the wheels were spinning at 40 miles per hour. As a result, attackers could disable a car while it was driving on the highway [Koscher10].

2.5 Brakes

Attackers are also able to engage breaks selectively and even prevent braking. The researchers who tested it out were unable to find a manual override to these attacks. They also tested it out on an actual runway and verified that the attacks are possible [Koscher10]. These attacks can be fatal for users.

The researchers who carried out the above tests also created a few composite attacks. Composite attacks are attacks that manipulate several components at the same time. In one example, the researchers implemented a speedometer attack which displayed an underestimate of the actual speed. It would be a subtle attack that could cause drivers to drive faster than expected. Another composite attack would be one where all of a car’s lights turn off at once. If a user is driving at night, an attacker can suddenly force all lights to turn and stay off. These composite attacks were tested on a runway and confirmed to be valid. Up to this point, these attacks require access to the CAN network which means attackers require access to the On Board Diagnostics (OBD-II) port of the car. When Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek, two researchers, showed what they can control in a Ford Escape, Ford responded that the auto industry focus is to “prevent hacking from a remote wireless device outside of the vehicle” [Greenberg13]. As such, the question remains: Can you remotely attack/control a car?

3. Remote Attacks

The same researchers who carried out the initial research expanded their objective. In a second paper they aimed to explore remote attacks upon cars [Checkoway11]. The attack surface is broken up into four components:

• Direct Physical Access (already covered)

• Indirect Physical Access

• Short-range Wireless Access

• Long-range Wireless Access

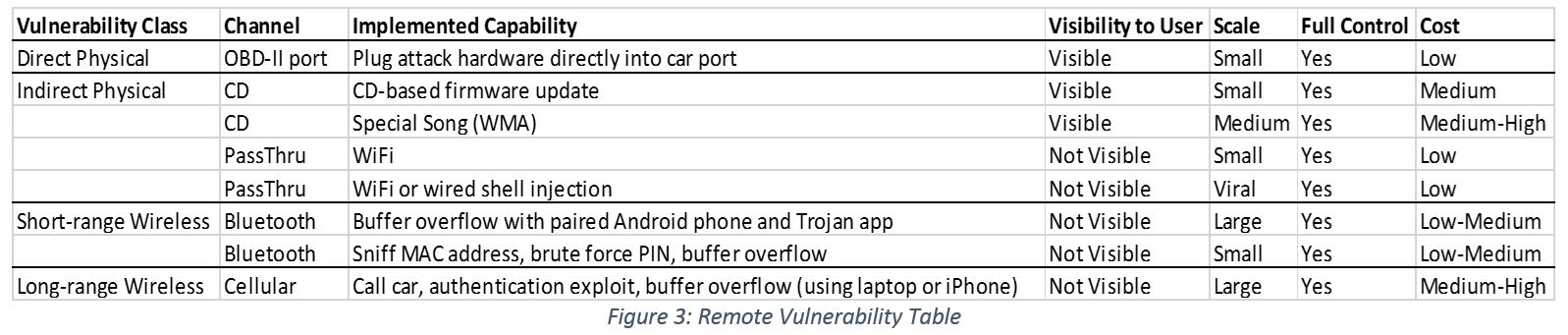

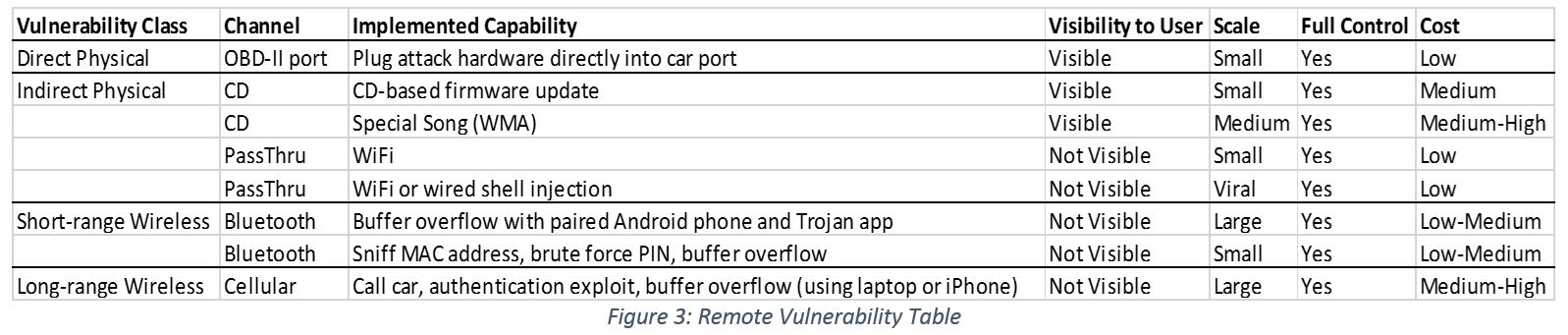

Figure 3 details the different methods explored – note that full compromise is possible for all methods:

3.1 Direct Physical

The first half of this paper focused on what was possible if you had access to the inner workings of the car. The OBD-II port of the car is a simple entry point for attackers to start sending CAN messages to manipulate the ECUs. This method requires physical access to the car and as a result, scales poorly and is hard to implement without detection.

3.2 Indirect Physical

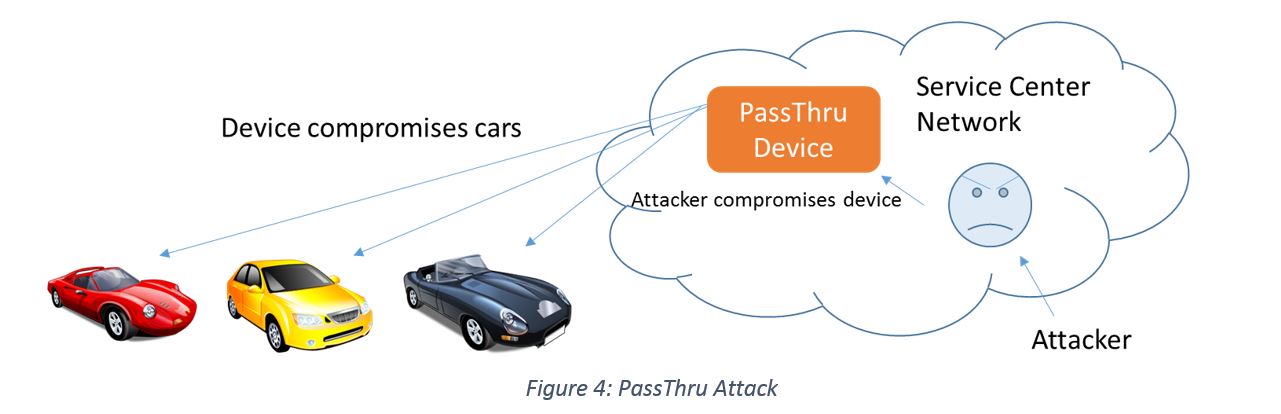

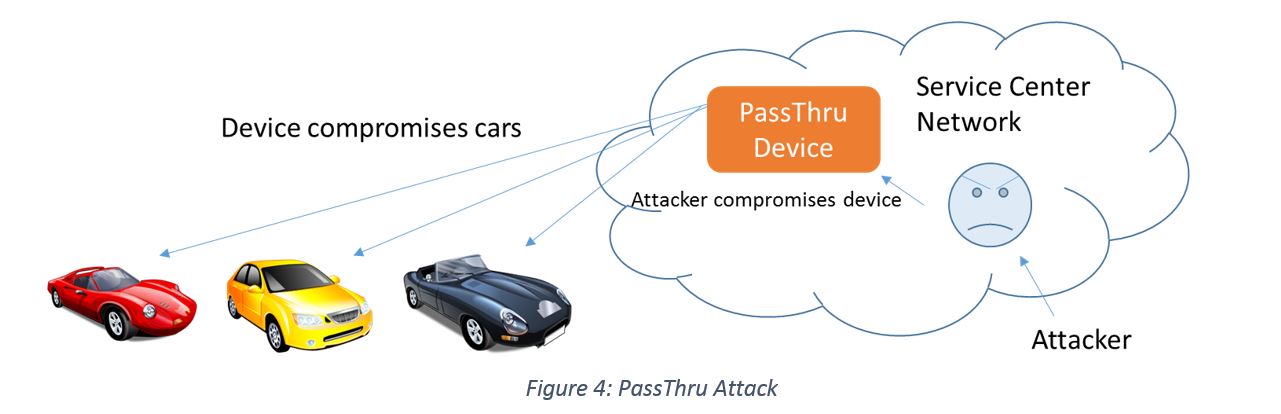

Indirect physical focuses on two main channels, CD and PassThru device. The researchers realized that they could “modify a WMA audio file such that, when burned onto a CD, plays perfectly on a PC but sends arbitrary CAN packets of our choosing when played by a car’s media player” [Checkoway11]. The other channel originates from a 2004 Environment Protection Agency mandate that all cars must support the “PassThru” standard.  The standard is basically a “Windows DLL that communicates over a wired or wireless network” with the PassThru device. These devices are used at service centers and are used with software for reprogramming or diagnostics purposes. The PassThru device plugs directly into the OBD-II port and allows communication with the car’s internal network. This connection makes the PassThru device a very attractive target for attackers. Researchers looking at a commonly used PassThru device discovered vulnerabilities that allowed attackers to connect to the devices if they are on the same network. Additionally, they discovered if the PassThru device is connected to a car, they can reprogram the car. The researchers wrote code to compromise the PassThru device and subsequently send “pre-programmed messages over the CAN bus whenever a technician connects the PassThru device to a car” as shown in Figure 4. They even took it a step further by turning the malware into a worm which seeks out other nearby PassThru devices [Checkoway11]. As a result, this attack can be implemented on a large scale at low cost.

The standard is basically a “Windows DLL that communicates over a wired or wireless network” with the PassThru device. These devices are used at service centers and are used with software for reprogramming or diagnostics purposes. The PassThru device plugs directly into the OBD-II port and allows communication with the car’s internal network. This connection makes the PassThru device a very attractive target for attackers. Researchers looking at a commonly used PassThru device discovered vulnerabilities that allowed attackers to connect to the devices if they are on the same network. Additionally, they discovered if the PassThru device is connected to a car, they can reprogram the car. The researchers wrote code to compromise the PassThru device and subsequently send “pre-programmed messages over the CAN bus whenever a technician connects the PassThru device to a car” as shown in Figure 4. They even took it a step further by turning the malware into a worm which seeks out other nearby PassThru devices [Checkoway11]. As a result, this attack can be implemented on a large scale at low cost.

3.3 Short-range Wireless

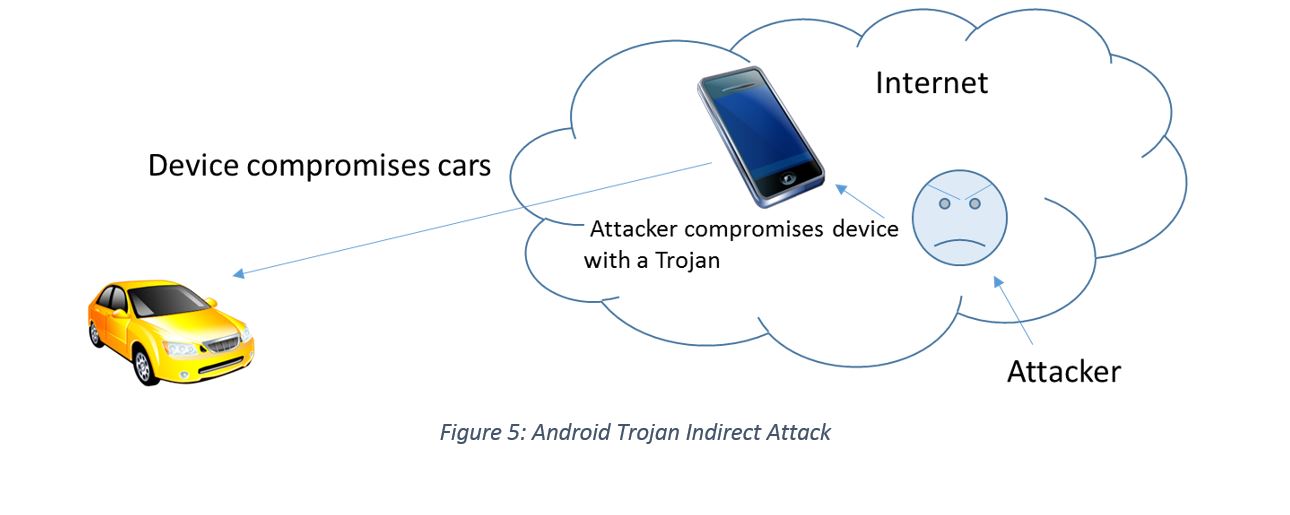

The majority of cars use Bluetooth for a range of reasons from playing music to hands-free calling. As a result, Bluetooth is a major component of the telematics unit. Many researchers have reverse-engineered the telematics ECU, and they found the code to be insecure and vulnerable [Kapersky14]. The researchers divided the short-range wireless vulnerabilities into two subcategories, direct and indirect. In this case, indirect means the attacker would gain access to the system through a user’s phone as shown in Figure 5. The attacker will have to infect the user’s phone with a Trojan which in turn delivers the attack when the phone connects to the car. Direct short-range wireless attacks involve learning the car’s Bluetooth MAC address and brute forcing the PIN required for connection.  Once connected, attackers can exploit the poorly coded telematics ECU and compromise the car. The phone Trojan can easily be spread on a larger scale without detection while the second attack cannot be scaled up easily [Checkoway11].

Once connected, attackers can exploit the poorly coded telematics ECU and compromise the car. The phone Trojan can easily be spread on a larger scale without detection while the second attack cannot be scaled up easily [Checkoway11].

3.4 Long-range Wireless

Some cars come with built in telematics units. This allows the car to use cellular networks to assist the users. For example, the car can automatically call for help if it detects a crash. The researchers discovered that calling the car repeatedly will eventually bypasses the authentication and exploit a buffer overflow vulnerability, allowing an attacker to force the car to download extra code from the Internet. Similarly, attackers can encode an audio file with the exploit, call a car, play the song into the microphone, and compromise the car [Checkoway11].

4. Future Outlook

While it may seem that modern cars are vulnerable in many ways, this part of the automobile industry is brand new and has not faced much adversarial pressure. This early research is meant to bring attention to what is possible before it is discovered too late [InfoSec14]. As autonomous cars seem more and more of a possibility, extra security complexities added by the multitude of sensors and cameras have to be considered [Vanderbilt12]. Recently, groups of security researchers have begun to band together to draw attention to safety concerns among automobiles. One such group called I am The Cavalry, formed in 2013, recently published a Five Star Automotive Cyber Safety Program at Def Con 22 [IamTheCavalry14]. The five key components the group highlights are:

• Safety by Design

• Third-Party Collaboration

• Evidence Capture

• Security Updates

• Segmentation and Isolation

4.1 Safety by Design

This trend is emerging across all technology fields. Instead of focusing on end product functionality, security is beginning to take priority especially after recent information breaches and the overall vulnerability of our infrastructure. As technology advances, architects and designers need to consider the safety aspect of the product. For automobiles, as the world moves closer towards automated cars, manufacturers will really need to focus on minimizing the huge attack surface currently present.

4.2 Third-Party Collaboration

No one is perfect in the security information industry especially when it comes to complex systems like a self-driving car. The only way to secure systems are to consistently try to break them in all kinds of ways. As such, I am The Cavalry believes that automobile manufacturers should be more transparent in their work by inviting third party researchers to find flaws and security risks. This third party collaboration is important because a third party would not have the same financial incentives to cut corners or to ignore safety.

4.3 Evidence Capture

I am The Cavalry puts an emphasis on collecting data from failures enabling the system to be improved quickly and effectively. However, this relies upon a strong logging system. Examples of this already implemented would include the black boxes within airplanes which can survive extreme conditions and provide valuable data to prevent further crashes in the future. Automobile manufacturers should take a similar amount of effort to learn what happened in an accident and aim to stop it from happening again [IamTheCavalry14].

4.4 Security Updates

As with any system there will always be fixes and patches to the code. Cars tend to be a long-term investment, the software needs to be kept secure and up-to-date. Building a system to allow easy and quick patching will be critical to keeping cars secure. Unfortunately, a patching system also frequently becomes the target of attacks. As a result, the patching system has to be extremely secure.

4.5 Segmentation and Isolation

With the advent of self-driving cars, in-car entertainment will grow as well. I am The Cavalry believes that automobile manufacturers should never intertwine the two systems. Currently, as described earlier in the paper, a song played over the phone can compromise the car. Manufacturers need to focus on separating the critical system and the entertainment system such that if the entertainment system were compromised, the attacker would not be able to affect the other system [Braga14].

5. Summary

The complexities of a self-driving or smart vehicle requires a lot cooperation between many different entities. As a result, security has to blanket everything as well. Any piece even as small as an inspection tool such as the PassThru device can be a point-of-failure that leads to a fully compromised car. Now that research has shown what is possible, the industry as a whole will need to move together and prioritize security. Increasing awareness around security is only the first step towards securing our future infrastructure.

References

[Checkoway11] Checkoway, Stephen and Koscher, Karl. “Comprehensive Experimental Analyses of Automotive Attack Surfaces”. Center For Automotive Embedded Systems Security. 2011,

http://www.autosec.org/pubs/cars-usenixsec2011.pdf

Even though this article is a bit older, it is one of the only known papers to remotely compromise a car in multiple ways.

[Koscher10] Koscher, Karl and Checkoway, Stephen. “Experimental Security Analysis of a Modern Automobile”. Center For Automotive Embedded Systems Security. 2010,

http://www.autosec.org/pubs/cars-oakland2010.pdf

One of the first and only papers documenting multiple attacks on a vehicle after getting access to the internal network of the car.

[Miller14] Miller, Charlie and Valasek, Chris. “Adventures in Automotive Networks and Control Units”. Black Hat USA 2014,

http://illmatics.com/car_hacking.pdf

A separate pair of researchers who looked at hacking two different cars and documented their findings.

[Vanderbilt12] Vanderbilt, Tom, “Let the Robot Drive: The Autonomous Car of the Future Is Here”, Wired Inc. January 20th, 2012,

http://www.wired.com/2012/01/ff_autonomouscars/all/

An in-depth article describing autonomous cars, how the function, and why they are going to be the future.

List of Terms

ECU – Electronic Control Unit

LIDAR – Light Detection and Ranging System

CAN – Control Area Network

DoS – Denial of Service

PSCM – Power Steering Control Module

BCM – Body Control Module

OBD-II – On-board Diagnostics Port 2

Last Modified: December 1, 2014

This and other papers on current issues in network security

are available online at http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-14/index.html

Back to Raj Jain's Home Page

Additionally, with the introduction of autonomous cars there will be advanced sensors such as the Light Detection and Ranging system (LIDAR), wheel encoders, infrared camera, etc [Vanderbilt12]. These sensors also rely on ECUs to process the information and make rapid decisions. This paper examines what is possible if malicious attackers have access to the car’s internal network, how they can remotely attack a car, and how the industry should move forward as autonomous cars become more and more of a reality.

Additionally, with the introduction of autonomous cars there will be advanced sensors such as the Light Detection and Ranging system (LIDAR), wheel encoders, infrared camera, etc [Vanderbilt12]. These sensors also rely on ECUs to process the information and make rapid decisions. This paper examines what is possible if malicious attackers have access to the car’s internal network, how they can remotely attack a car, and how the industry should move forward as autonomous cars become more and more of a reality.

The standard is basically a “Windows DLL that communicates over a wired or wireless network” with the PassThru device. These devices are used at service centers and are used with software for reprogramming or diagnostics purposes. The PassThru device plugs directly into the OBD-II port and allows communication with the car’s internal network. This connection makes the PassThru device a very attractive target for attackers. Researchers looking at a commonly used PassThru device discovered vulnerabilities that allowed attackers to connect to the devices if they are on the same network. Additionally, they discovered if the PassThru device is connected to a car, they can reprogram the car. The researchers wrote code to compromise the PassThru device and subsequently send “pre-programmed messages over the CAN bus whenever a technician connects the PassThru device to a car” as shown in Figure 4. They even took it a step further by turning the malware into a worm which seeks out other nearby PassThru devices

The standard is basically a “Windows DLL that communicates over a wired or wireless network” with the PassThru device. These devices are used at service centers and are used with software for reprogramming or diagnostics purposes. The PassThru device plugs directly into the OBD-II port and allows communication with the car’s internal network. This connection makes the PassThru device a very attractive target for attackers. Researchers looking at a commonly used PassThru device discovered vulnerabilities that allowed attackers to connect to the devices if they are on the same network. Additionally, they discovered if the PassThru device is connected to a car, they can reprogram the car. The researchers wrote code to compromise the PassThru device and subsequently send “pre-programmed messages over the CAN bus whenever a technician connects the PassThru device to a car” as shown in Figure 4. They even took it a step further by turning the malware into a worm which seeks out other nearby PassThru devices  Once connected, attackers can exploit the poorly coded telematics ECU and compromise the car. The phone Trojan can easily be spread on a larger scale without detection while the second attack cannot be scaled up easily

Once connected, attackers can exploit the poorly coded telematics ECU and compromise the car. The phone Trojan can easily be spread on a larger scale without detection while the second attack cannot be scaled up easily