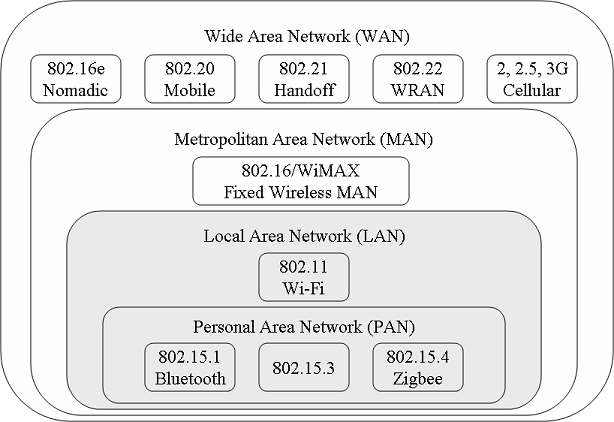

Fig. 1: Wireless Standards

This paper presents a survey on the various power saving techniques used in wireless networking today. The work presented covers topics ranging from the use of energy harvesting techniques at the physical layer to partitioning the load of power hungry computations across multiple devices at the application layer. While research in this area continues to grow, few standards have yet to emerge that incorporate the use of each of these techniques. De facto standards do exist, however, and tend to be driving the development of power aware devices in industry at the moment.

This paper explores the various techniques used for preserving the energy consumed at each layer of a wireless networking protocol stack. The types of wireless networks considered include Wireless Local Area Networks (WLANs), Wireless Personal Area Networks (WPANs), and Wireless Sensor Networks. Existing standards for performing power management in each of these networks are discussed, and their effective use is analyzed. The role that these standards play in industry as well as the role played by current research in this area is also introduced.

Many differences exist between wireless networks and tradition wired ones. The most notable difference between these networks is the use of the wired medium for communication. The promise of a truly wireless network is to have the freedom to roam around anywhere within the range of the network and not be bound to a single location. Without proper power management of these roaming devices, however, the energy required to keep these devices connected to the network over extended periods of time quickly dissipates. Users are left searching for power outlets rather than network ports, and becoming once again bound to a single location.

A plethora of power management schemes have been developed in recent years in order to address this problem. Solutions exist at every layer of the traditional network protocol stack, and each of them promises to provide their own level of energy savings. This paper takes a look at the different techniques used at each layer and examines the standards that have emerged as well as products being developed that are based on them. It focuses on the subset of wireless networking that deals with Wireless Local Area Networks (WLAN) and Wireless Personal Area Networks (WPAN). As a subset of WPANs known as LR-WPANs that require very low power operation at very low data rates, techniques used in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) are given particular focus.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of WLANs, WPANs, and WSNs, including a discussion of how each type of network differs in terms of their requirements for performing power management. Section 3 follows with an introduction to the different power management techniques used within the various network protocol layers in each type of network. Section 4 discusses standards for each type of network that have been developed to use these different techniques. Section 5 talks about the recent advances that have been made in the field of power management, followed by a short description of the products available from industry which take advantage of this research in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 provides a summary of the entire paper, with references and a list of the abbreviations used throughout the paper following at the end.

Wireless networks have been a hot topic for many years. Their potential was first realized with the deployment of cellular networks for use with mobile telephones in the late 1970's. Since this time, many other wireless wide are networks (WWANs) have begun to emerge, along with the introduction of wireless Metropolitan Area Networks (WMANs), wireless Local Area Network (WLANs), and wireless Personal Area Networks (WPANs). Fig. 1 shows a number of standards that have been developed for each of these types of networks.

Fig. 1: Wireless Standards

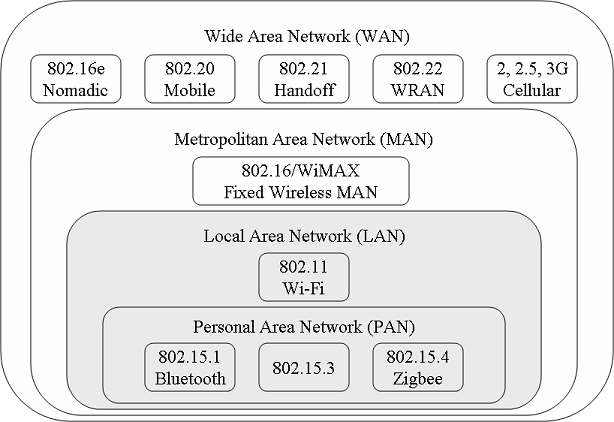

If they are to have any hope of long term usability, the power consumed by individual nodes in each of these networks needs to be managed efficiently. Although performing this power management is important for each of these types of networks, this paper focuses primarily on the power management schemes used by WLANs and WPANs. The following two subsections give a brief overview of these two types of networks, along with a description of how they differ from one another in terms of their power management requirements. The final subsection is dedicated to the introduction of a subset of WPANs, known as wireless sensor networks (WSNs). Wireless sensor networks are specifically designed for very low power operation and thus deserve this degree of special attention. Fig. 2 shows how these different types of networks compare in terms of data rate and power consumption. The [Ieee802.15.4] standard shown in the figure is the one most widely used by wireless sensor networks.

Fig. 2: Power Consumption in IEEE 802 based networks

Most wireless LANs are based on the IEEE 802.11 standard [Ieee802.11] depicted in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. This standard is also known as WiFi (Wireless Fidelity), and provides functionality for wireless devices to communicate in a way similar to the way they would on a traditional wired LAN. Devices in these networks normally operate at a higher data rate than for devices existing in a WPAN. They are usually made to communicate over longer distances as well. Because of this higher data rate and longer communication range (higher transmission power), they also tend to consume more power. To reduce the power consumed, a power management scheme known as PSM is built into the 802.11 standard. Section 4.1 talks about this power management scheme in more detail.

Many variations of the 802.11 standard have begun to emerge over the past few years, each with its own set of enhancements over the original 802.11 standard. Some of these improvements are for enhanced Quality of Service (802.11e), Security (802.11i), Throughput (802.11n), as well as dynamic frequency selection and transmission power control (802.11h). Of all the variations, however, only [Ieee802.11h] deals with improving the power management capabilities of 802.11 in any way. As will be shown in Section 3.3, transmission power control is a method of controlling the topology of a network by reducing the power at which certain nodes in the network are allowed to transmit. However, the 802.11h enhancement standard does not explicitly define a policy for implementing a transmission power control policy; it only provides the facility for doing so.

While it is desirable for devices in a WLAN or a WPAN to consume as little power as possible it is imperative for devices in a wireless sensor network to do so. WSNs are made up of a large number of tiny low-cost, low-power, multi-functional devices used for extracting data from the environment around them. They are capable of taking sensor readings from the environment, processing that data, and communicating it back to some central location for further processing. They can essentially be thought of as extensions of the Internet into the physical world. In many situations it is desirable that the devices making up a WSN are deployed into the environment and left to run on their own accord for many months or even years. Without careful power management of these devices, such deployments would not be possible.

The WPAN standard designed to work with WSNs is 802.15.4 [Ieee802.15.4]. As shown is Fig. 2, 802.15.4 is not only the standard that consumes the least amount of power, but also the one having the lowest data rate. Many of the power management techniques discussed later on in this paper have been developed specifically with WSN applications in mind. Section 4.2 discusses the [Zigbee] specification developed to work on top of the 802.15.4 standard to further reduce the power consumed in WSNs.

The previous section discussed WLANs and WPANs and the various standards that exist for them. The differences between each type of network were introduced with an emphasis put on their requirements for performing power management that each of them have. This section discusses the various power management techniques used by these standards for reducing the power consumed in each type of network. Many of the techniques introduced in this section do not appear in any of these standards, but are used in common practice to reduce the power of devices in both WLANs and WPANs. These techniques exist from the application layer all the way down to the physical layer of a traditional networking protocol stack. Techniques specific to a particular type of network are annotated as appropriate.

At the application layer a number of different techniques can be used to reduce the power consumed by a wireless device. A technique known as load partitioning allows an application to have all of its power intensive computation performed at its base station rather than locally [Jones01]. The wireless device simply sends the request for the computation to be performed, and then waits for the result. Another technique uses proxies in order to inform an application to changes in battery power. Applications use this information to limit their functionality and only provide their most essential features. This technique might be used to suppress certain "unnecessary" visual effects that accompany a process [Jones01]. While these techniques may be adapted to work with any application that wishes to support them, a number of techniques also exist for specific classes of applications.

Some applications are so common that it is worth exploring techniques that specifically deal with reducing the power consumed while running them. Two of the most common such applications include database operations and video processing [Jones01]. For database systems, techniques are explored that are able to reduce the power consumed during data retrieval, indexing, as well as querying operations. In all three cases, energy is conserved by reducing the number of transmissions needed to perform these operations. For video processing applications, energy can be conserved using compression techniques to reduce the number of bits transmitted over the wireless medium. Since performing the compression itself may consume a lot of power, however, other techniques that allow the video quality to become slightly degraded have been explored in order to reduce the power even further. Please refer to [Negri04] for a more complete list of application specific power management schemes.

The various techniques used to conserve energy at the transport layer all try to reduce the number of retransmissions necessary due to packet losses from a faulty wireless link [Jones01]. In a traditional (wired) network, packet losses are used to signify congestion and require backoff mechanisms to account for this. In a wireless network, however, losses can occur sporadically and should not immediately be interpreted as the onset of congestion. The TCP-Probing [Tsaoussidis00] and Wave and Wait Protocols [Zhang01] have been developed with this knowledge in mind. They are meant as replacements for traditional TCP, and are able to guarantee end-to-end data delivery with high throughput and low power consumption.

Power management techniques existing at the network layer are concerned with performing power efficient routing through a multi-hop network [Jones01] [Manoj04] [Karl03]. They are typically either backbone based, topology control based, or a hybrid of them both. In a backbone based protocol (sometimes also referred to as Charge Based Clustering), some nodes are chosen to remain active at all times (backbone nodes), while others are allowed to sleep periodically. The backbone nodes are used to establish a path between all source and destination nodes in the network. Any node in the network must therefore be within one hop of at least one backbone node, including backbone nodes themselves. Energy savings are achieved by allowing non-backbone nodes to sleep periodically, as well as by periodically changing which nodes in fact make up the backbone.

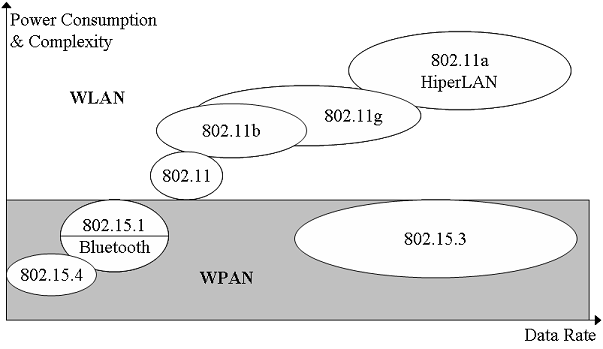

Fig. 3: Backbone based routing

Fig. 3 shows how packets would be routed from node 3 to node 4 and from node 1 to node 2 using the backbone that has been established. Black nodes signify backbone nodes, while numbered nodes signify non-backbone nodes. Solid lines indicate paths along which a packet may travel, while dashed ones show paths that will not be followed. Given this backbone structure, packets traveling from node 3 to node 4 will have to travel through 4 different backbone nodes before reaching their destination. If node 5 had been chosen as a backbone node as well, packets would only have had to traverse through 2.

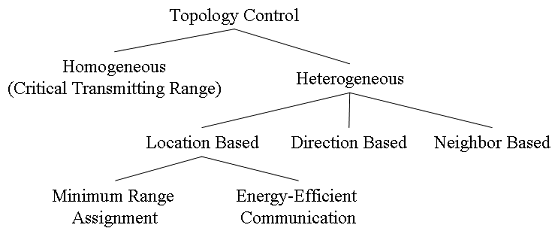

Topology based routing protocols achieve energy savings in a different way. Their goal is to reduce the transmission power of all nodes in a network such that the network remains connected, but all nodes operate with the lowest transmission power possible. In a homogeneous network, this means that the transmission powers of all nodes are adjusted so that they are just within range of their nearest one-hop neighbor. In heterogeneous networks (i.e. networks with nodes of different type, power limitations, etc.) the transmission powers may be adjusted according to the needs of that network. A summary of the different types of topology based protocols that exist can be seen in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4: Topology based routing protocols

As seen in the figure, certain location based topology control protocols attempt to use the topology of the network to provide the most energy efficient communication path possible. These protocols produce a sort of "Localized Power-Aware Routing" mechanism for the network. In some cases, providing this path means taking a larger number of hops through the network than would otherwise be taken when transmitting directly from one node to another. While this may seem counterintuitive at first, it makes sense if the amount of energy expended in transmitting to a node very far away is significantly greater than the energy expended when transmitting between a large number of nodes that are within closer range of one another. The rational behind the other topology based protocols found in Fig. 4 can be found in [Bao03].

Transmission power control schemes are combined with backbone based ones to produce a hybrid of them both. Using hybrid based protocols, the benefits of both backbone based and topology based routing protocols can be achieved simultaneously. Section 5.1 explores a number of different power efficient routing protocols that use the ideas presented in this section.

The two most common techniques used to conserve energy at the link layer involve reducing the transmission overhead during the Automatic Repeat Request (ARQ) and Forward Error Correction (FEC) schemes. Both of these schemes are used to reduce the number of packet errors at a receiving node. By enabling ARQ, a router is able to automatically request the retransmission of a packet directly from its source without first requiring the receiver node to detect that a packet error has occurred. Results have shown that sometimes it is more energy efficient to transmit at a lower transmission power and have to send multiple ARQs than to send at a high transmission power and achieve better throughput. Integrating the use of FEC codes to reduce the number of retransmissions necessary at the lower transmission power can result in even more energy savings. Power management techniques exist that exploit these observations [Jones01].

Other power management techniques existing at the link layer are based on some sort of packet scheduling protocol [Alghamdi05]. By scheduling multiple packet transmission to occur back to back (i.e. in a burst), it may be possible to reduce the overhead associated with sending each packet individually. Preamble bytes only need to be sent for the first packet in order to announce it presence on the radio channel, and all subsequent packets essentially "piggyback" this announcement. Packet scheduling algorithms may also reduce the number of retransmissions necessary if a packet is only scheduled to be sent during a time when its destination is known to be able to receive packets. By reducing the number of retransmissions necessary, the overall power consumption is consequently reduced as well.

Power saving techniques existing at the MAC layer consist primarily of sleep scheduling protocols. The basic principle behind all sleep scheduling protocols is that lots of power is wasted listening on the radio channel while there is nothing there to receive. Sleep schedulers are used to duty cycle a radio between its on and off power states in order to reduce the effects of this idle listening. They are used to wake up a radio whenever it expects to transmit or receive packets and sleep otherwise. Other power saving techniques at this layer include battery aware MAC protocols (BAMAC) [Jayashree04] in which the decision of who should send next is based on the battery level of all surrounding nodes in the network. Battery level information is piggy-backed on each packet that is transmitted, and individual nodes base their decisions for sending on this information.

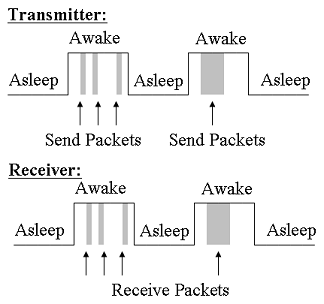

Sleep scheduling protocols can be broken up into two categories: synchronous and asynchronous [Zheng03] [Dam03]. Synchronous sleep scheduling policies rely on clock synchronization between nodes all nodes in a network. As seen in Fig. 5., senders and receivers are aware of when each other should be on and only send to one another during those time periods. They go to sleep otherwise.

Fig. 5: Synchronous sleep scheduler

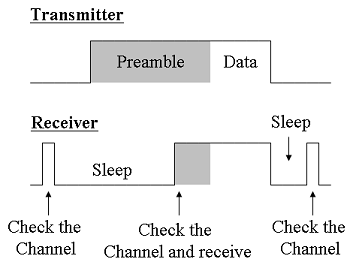

Asynchronous sleep scheduling, on the other hand, does not rely on any clock synchronization between nodes whatsoever. Nodes can send and receive packets whenever they please, according to the MAC protocol in use. Fig. 6 shows how two nodes running asynchronous sleep schedulers are able to communicate.

Fig. 6: Asynchronous sleep scheduler

Nodes wake up and go to sleep periodically in the same way they do for synchronous sleep scheduling. Since there is no time synchronization, however, there must be a way to ensure that receiving nodes are awake to hear the transmissions coming in from other nodes. Normally preamble bytes are sent by a packet in order to synchronize the starting point of the incoming data stream between the transmitter and receiver. With asynchronous sleep scheduling, a significant number of extra preamble bytes are sent per packet in order to guarantee that a receiver has the chance to synchronize to it at some point. In the worst case, a packet will begin transmitting just as its receiver goes to sleep, and preamble bytes will have to be sent for a time equal to the receiver's sleep interval (plus a little more to allow for proper synchronization once it wakes up). Once the receiver wakes up, it synchronizes to these preamble bytes and remains on until it receives the packet.

Unlike the power efficient routing protocols introduced in section 3.3, it doesn't make sense to have a hybrid sleep scheduling protocol based on each of the two techniques. The energy savings achieved using each of them varies from system to system and application to application. One technique is not "better" than the other in this sense, so efforts are being made to define exactly when each type should be used. Section 5.2 explores this concept further.

At the physical layer, techniques can be used to not only preserve energy, but also generate it. Proper hardware design techniques allow one to decrease the level of parasitic leak currents in an electronic device to almost nothing [Jacome03]. These smaller leakage currents ultimately result in longer lifetimes for these devices, as less energy is wasted while idle. Variable clock CPUs, CPU voltage scaling, flash memory, and disk spin down techniques can also be used to further reduce the power consumed at the physical layer [Jones01] [Manoj04]. A technique known as Remote Access Switch (RAS) can be used to wake up a receiver only when it has data destined for it. A low power radio circuit is run to detect a certain type of activity on the channel. Only when this activity is detected does the circuit wake up the rest of the system for reception of a packet. A transmitter has to know what type of activity needs to be sent on the channel to wake up each of its receivers. [Manoj04]

Energy harvesting techniques allow a device to actually gather energy from its surrounding environment. Ambient energy is all around in the form of vibration, strain, inertial forces, heat, light, wind, magnetic forces, etc [Brown06]. Energy harvesting techniques allow one to harness this energy and either convert it directly into usable electric current or store it for later use within an electrical system. In section 5.3 the latest technological advances in both low power design and energy harvesting techniques will be introduced.

In the previous section, various techniques were explored that enable energy to be conserved at various layers within the wireless networking protocol stack. Some techniques were looked at in greater detail than others, and some techniques existing at the overall system level were not discussed at all. These power management schemes involve controlling the power state for peripheral devices such as the display or hard disk on a laptop computer. Others include cycling through the use of multiple batteries on a device in order to increase the overall lifetime of each individual one. Since these techniques do not explicitly exist at any single layer within the wireless networking protocol stack itself, they have been left out of this discussion. For more information on these and other power management techniques not discussed in the previous section, please refer to chapter eleven of [Manoj04] and its corresponding list of references.

The following section focuses on the use of the techniques introduced in the previous section for defining the various power management schemes built into the IEEE 802 standards discussed in section 2. As the IEEE standards body only concerns itself with defining the various MAC layer protocols for the 802 family of wireless networks, the standards discussed in this section only make use of the sleep scheduling protocols discussed previously. The standards that exist for WLANs (802.11-PSM), WPANs (Bluetooth), and WSNs (802.15.4/Zigbee) are all introduced separately.

The IEEE 802.11 standard specifies how communication is achieved for wireless nodes existing in a Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN). Part of this standard is dedicated to describing a feature known as Power Save Mode (PSM) that is available for nodes existing in an infrastructure based 802.11 WLAN [Ieee802.11-PSM]. PSM is based on a synchronous sleep scheduling policy, in which wireless nodes (stations) are able to alternate between an active mode and a sleep mode. As a wireless station using PSM first joins an infrastructure based WLAN, it must notify its access point that it has PSM enabled. The access point then synchronizes with the PSM station allowing it to begin running its synchronous sleep schedule. When packets arrive for each of these PSM stations, the access point buffers them until their active period comes around again. At the beginning of each active period, a beacon message is sent from the access point to each wireless station in order to notify them of these buffered packets. PSM stations then request these packets and they are forwarded from the access point. Once all buffered frames have been received, a PSM station resumes with its sleep schedule wherever it left off. Whenever a PSM station has data to send, it simply wakes up, sends its packet, and then resumes its sleep schedule protocol as appropriate.

Although this feature of 802.11 networks is readily available on all devices implementing the full 802.11 specification, it is not very widely used. Many studies have been done to investigate the effects of using PSM and other power saving techniques for WLANs [Simunic05][Bononi01] [Molta05][Gruteser01] [Anastasi04][Chen04]. They all conclude that the throughput achieved with these techniques is significantly less than with them disabled. While PSM may significantly reduce the energy consumed by a wireless station, many users prefer to sacrifice these power savings for an increase in performance.

The 802.15.1 standard [Bluetooth] provides provisions for power management as well. Wireless nodes in a Bluetooth network are organized into groups known as piconets, with one node dedicated as the master node and all others as slave nodes. Up to seven active nodes can exist in a piconet at any given time, with up to 256 potential members (249 inactive). All nodes operate using a synchronous sleep scheduling policy in order to exchange data. A beacon messaging system similar to the one described in Section 4.1 for 802.11 based networks is used to exchange messages between slave nodes and their master. All nodes are able to communicate with all other nodes within the Piconet, but messages between slaves must be sent exclusively through the master node.

Bluetooth defines eight different operational states, 3 of which are dedicated to low power operations. These three low power states are known as Sniff, Hold, and Park. While in the Sniff state, an active bluetooth device simply lowers its duty cycle and listens to the piconet at a reduced rate. When switching to the Hold state, a device will shut down all communication capabilities it has with a piconet, but remain "active" in the sense that it does not give up its access to one of the seven active slots available for devices within the piconet. Devices in the Park state disable all communication with the piconet just as in the Hold state, except that they also relinquish their active node status.

The 802.15.4 [Ieee802.15.4] wireless networking standard provides low data rate, low power communication that is ideal for wireless sensor networking applications. It too is based on a synchronous sleep scheduling policy that periodically wakes nodes up and puts them to sleep in order to exchange data. The difference between this standard and the others is in the frequency with which nodes wake up, and the data rate (and correspondingly the required transmission power) with which they transmit data. A low power protocol stack called [Zigbee] has been developed on top of the 802.15.4 MAC layer in order to provide low power solutions for WSNs. As will be seen in section 6, many products for WSNs are being developed in industry with "Zigbee" compatibility as a very strong marketing point.

In addition to the standards that have been developed for low power communication in wireless networks, ongoing research continues to provide innovative solutions to this problem. This section discusses some of the more recent advances and provides references to some of the older ones. Since it is impossible to list every single power management protocol that has ever been developed for warless networking, only the most representative ones have been provided here.

Backbone based protocols such as ASCENT [CerpaXX] and SPAN [Chen02], utilize local rules to assess a node's connectivity with its neighbors and decide whether the node should stay active to join a communication backbone. These protocols focus on maintaining network connectivity, and are best suited for ad-hoc multihop networks running at high data rates.

In a wireless sensor network setting, nodes are not just concerned with communicating with one another, but also in maintaining proper sensing coverage. A number of hybrid based protocols for wireless sensor networks that achieve this goal have been explored most recently in PEAS [Ye03].

A number of different sleep scheduling protocols exist, each with their own set of advantages and disadvantages for different types of wireless networking systems/applications. While both 802.11 PSM [Ieee802.11-PSM] and S-MAC [Ye02] are synchronous sleep scheduling policies, they are targeted towards two very distinct wireless networking domains. 802.11 PSM targets high data rate wireless devices existing in an infrastructure based WLAN, while S-MAC targets very low data rate wireless sensing devices existing in a wireless sensor network. As stated before, however, even with these types of policies available, users tend to prefer higher throughput to the power savings they can achieve. One solution known as PAMAS (Power Aware Multi-Access Signaling) has proven to be very effective in reducing the power consumed in both types of networks [Singh98]. Using PAMAS, nodes are able to detect when a packet on the channel is destined for someone else and put themselves to sleep. PAMAS can be combined with some of the other sleep scheduling protocols discussed below to produce even more power savings.

An asynchronous sleep scheduling protocol known as Low Power Listening (LPL) [Polastre05] is quickly becoming the de facto standard for sleep scheduling policies in the world of wireless sensor networks. LPL operates just as any other asynchronous sleep scheduling protocol with one key difference. When LPL turns the radio on to check the channel for incoming packets, it does so very quickly (and reliably) so as to go back to sleep as quickly as possible. The time between each of these checks is known as a check interval. LPL only achieves significant power savings if many check intervals are allowed to pass before a packet is actually detected on the channel. This makes LPL ideal for the low data rate environment pertinent in wireless sensor networks.

While the protocols described above only scratch the surface on the number of sleep scheduling protocols that have been developed to date, they do provide a good reference to the different domains in which different types of sleep scheduling protocols are most applicable.

Traditionally, energy has been harvested through the use of solar panels attached to the periphery of a wireless device. These solar panels are made up of photovoltaic cells that convert sunlight directly into electrical current [Brown06]. The primary disadvantage of solar panels, however, is that they are large and that they require sunlight in order to work. In most wireless networking situations (but not all), it is not practical to be limited by such constraints. Laptops should not have bulky solar panels attached to them and only be operational outdoors, while nodes deployed for a wireless sensor network to take wind measurements in the Sahara desert may welcome such a technology.

Most recently, advances have been made with a technology involving the use of piezoelectric materials. Piezoelectricity is the ability to create an electric current by suppressing certain types of crystal to mechanical stress. The primary advantages that piezoelectric materials have over solar panels is that they are small, do not require access to direct sunlight, and they operate with about a 70% mechanical to electrical transduction efficiency. Solar panels achieve only about 16-18% efficiency [Brown06].

While the science behind both solar energy harvesting and piezoelectric materials has been well understood for quite some time, their potential in the wireless networking domain are just now being realized. Section 6 discusses some of these applications and what products are being manufactured to support them.

Products are being developed that exploit the power conserving techniques discussed in the previous sections. Products that make use of both the standards as well as cutting edge research efforts are beginning to hit the market. Most of the newer products are within the realm of WPANs and WSNs, but some new power saving devices for WLANs keep appearing as well. This section discusses some of these products, and how they use the standards and protocols discussed in the previous section to achieve energy savings.

As stated previously, the PSM built into the 802.11 standard is not very widely used. Because of this fact, many of the products that claim to be completely 802.11 compliant do not even include this feature in their distribution. Products exploiting the techniques discussed throughout this paper for reducing the power consumed in WLANs is mostly being done at the application layer or system level. Wireless networking cards for use in WLANs are beginning to appear that claim to be more power efficient than their predecessors . Laptops are designed to shut down their displays and networking cards after a certain period of inactivity. Many applications are now being designed to implement the load partitioning algorithms discussed in Section 3.1. While these products do not exploit the full capability of the power management techniques discussed in this paper, they do allow an application to save as much power as possible, while still maintaining a high level of throughput. As time moves forward, it is anticipated that more and more products will begin to appear that find ways to balance these two conflicting needs.

Bluetooth devices have become increasingly popular over the last 10 years. A huge part of their success has been due to the extended battery life made possible through their 3 different low power modes of operation. Almost every computer, cell phone, PDA, GPS system, etc. that one can buy nowadays comes equipped with bluetooth technology enabled. The 802.15.3 standard has been developed to provide higher data rates than bluetooth for use with streaming multimedia applications. Products with this technology built into them are just now beginning to appear, and will most likely not begin to dominate the market until a few years from now. The power saving techniques used in these devices is based on the bluetooth technology and therefore employs some of the same power management techniques. Special purpose boots exploiting the use of piezoelectric materials are also being developed by the military in order to allow a soldier to simply click their heels together in order to power up the entire set of communications gear that they have within their PAN [Brown06].

Products aimed at structural health monitoring, industrial monitoring, home automation, etc., have been made possible by the use of the extremely low power 802.15.4/Zigbee standards. Chipcon [Chipcon]radio manufacturers produce radio chips with the 802.15.4 standard built into them. Companies such as Crossbow Technologies [Xbow] and Motiv [Motiv] lead the market in the manufacturing small wireless devices called motes for use in wireless sensor network applications. Intel has recently released a low power wireless sensor network platform that is ideal for monitoring manufacturing equipment in an industrial setting. As the field of WSNs is still fairly young, it is expected that many new application and products will begin to emerge over the next few years that exploit the research done in the field of power management for wireless networking in unprecedented ways. As long as the demand for lower power wireless devices is present, products will never stop being produced.

In this survey, a variety of different energy conserving techniques for wireless networks have been explored. Although the scope of this paper has been limited exclusively to WLANs and WPANs, many of the techniques presented are universal and can be used to perform power management in any type of network. A brief overview of each type of network has been given, including a description of a subset of WPANs known as Wireless Sensor Networks. It was shown that while WLANs and traditional WPANs may achieve longer lifetimes through the use of the power management techniques presented, low power design in WSNs is an essential feature and thus required particular focus in this paper.

The various power saving techniques used at each layer in the traditional networking protocol stack have been presented, and their applicability to each type of network has been analyzed. It was shown that all types of networks can benefit from sleep scheduling protocols, topology control mechanisms, and energy harvesting techniques. However, certain application specific power management schemes are strictly meant for either WLANs or WPANs exclusively.

The integration of some of the techniques into the IEE 802 standards that exist for WLANs and WPANs was presented, and a brief overview of how these techniques are used has been given. The 802.11 PSM has been shown to reduce the power consumed by nodes within a WLAN. In practice, however, the PSM feature provided by this standard is not used, as consumers prefer to have higher throughput rather than longer battery life on their wireless devices. Bluetooth devices on the other hand benefit greatly from the power saving features they provide, and have thus become very widely used over the past few years. Although the industry standard known as "Zigbee" has been developed to work on top of 802.15.4 enabled WSNs, research continues in this area due to the stringent power requirements that these types of networks impose.

It has been shown that the current research being conducted for power management in wireless networks has been focused developing better topology maintenance protocols, sleep scheduling protocols, and energy harvesting techniques. While each of these techniques provides power savings on their own, they can all be combined to achieve better performance than any one of them individually.

Products are just now being manufactured that exploit the use of these types of techniques. Bluetooth devices have achieved the most success in industry, with devices designed for WSNs following close behind. Power aware devices for WLANs have not achieved as much success because of the need for very high throughput in these types of networks. No one seems to want to save power if it means sacrificing performance.

The quest for the everlasting battery source has not yet produced any results. As long as there is the need to continue driving down the amount of energy consumed by a wireless device, more and more research will continue to be done in this field, more and more standards will continue to emerge, and more and more products will continue to be manufactured.

The references below are ordered by importance. Importance has been determined by the number of citations appearing in the text. Some of the references near the end of this section are not cited directly, but are provided here because they present useful information regarding power management in wireless networks. In many cases, these references have been referred to by one or more of the references cited directly in this document.

In most cases a clickable URL is provided to documents accessible through the Internet. For some shorter URLs, the URL itself is provided for easy reference. In cases where the title itself does not provide a summary of the contents of the paper itself, a brief description follows the citation.

[Jones01]

Christine E. Jones, Krishna M. Sivalingam, Prathima Agrawal, Jyh Cheng Chen.

A Survey of Energy Efficient Network Protocols for Wireless Networks.

Wireless Networks. Volume 7, Issue 4 (August 2001). Pg. 343-358. ISSN:1022-0038

[Manoj04]

B.S. Manoj, C. Siva Ram Murthy.

Ad Hoc Wireless Networks: Architectures and Protocols.

Prentice Hall, 2004. Chapter 11. ISBN:013147023X

[Karl03]

Holger Karl.

An Overview of Energy-Efficiency Techniques for Mobile Communication Systems.

TKN Technical Reports Series. Technische Universitaet Berlin, 2003.

http://www.tkn.tu-berlin.de/publications/papers/TechReport_03_017.pdf

[Ieee802.11]

IEEE 802.11 1999 Standard.

IEEE Standards for Information Technology --

Telecommunications and Information Exchange between Systems --

Local and Metropolitan Area Network --

Specific Requirements --

Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical

Layer (PHY) Specifications.

http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.11-1999.pdf

[Ieee802.11-PSM]

IEEE 802.11 PSM Standard.

Power Management for Wireless Networks.

Section 11.11.2: Power Management.

http://www.spirentcom.com/documents/841.pdf

[Ieee802.11h]

IEEE 802.11h 2003 Standard Enhancement.

IEEE Standard for Information technology --

Telecommunications and Information Exchange Between Systems--

LAN/MAN Specific Requirements --

Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC)

and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications:

Spectrum and Transmit Power Management Extensions in the 5GHz band in Europe.

http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.11h-2003.pdf

[Bluetooth]

IEEE 802.15.1 2005 Standard.

IEEE Standard for Information technology--

Telecommunications and information exchange between systems--

Local and metropolitan area networks--

Specific requirements. Part 15.1:

Wireless Medium Access Control (MAC)

and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications for Wireless Personal Area Networks (WPANs(tm))

.

http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.15.1-2005.pdf

[Ieee802.15.3]

IEEE 802.15.3 2005 Standard.

IEEE Standard for Information technology--

Telecommunications and information exchange between systems--

Local and metropolitan area networks--

Specific requirements Part 15.3:

Wireless Medium Access Control (MAC)

and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications for

High Rate Wireless Personal Area Networks (WPAN).

http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.15.3-2003.pdf

[Ieee802.15.4]

IEEE 802.15.4 2003 Standard.

IEEE Standard for Information technology--

Telecommunications and information exchange between systems--

Local and metropolitan area networks--

Specific requirements Part 15.4:

Wireless Medium Access Control (MAC)

and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications for

Low Rate Wireless Personal Area Networks (LR-WPANs).

http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.15.4-2003.pdf

[Zigbee]

Zigbee Specification.

Industry Standard for 802.15.4 (LR-WPANs).

http://www.zigbee.org/en/spec_download/download_request.asp

[Negri04]

Luca Negri, Domenico Barretta, William Fornaciari.

Pervasive computing: Application-level power management in pervasive computing systems: a case study.

Proceedings of the 1st conference on Computing frontiers.

Pg. 78-88. 2004. ISBN:1-58113-741-9.

[Tsaoussidis00]

V. Tsaoussidis, H. Badr.

TCP-Probing: Towards an Error Control Schema with Energy and Throughput Performance Gains.

In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE Conference on Network Protocols,

Japan, November 2000.

http://citeseer.csail.mit.edu/tsaoussidis00tcpprobing.html

[Zhang01]

C. Zhang and V. Tsaoussidis.

TCP Real: Improving Real-time Capabilities of TCP over Heterogeneous Networks.

In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE/ACM NOSSDAV 2001,

New York, 2001.

http://citeseer.csail.mit.edu/zhang01tcpreal.html

[Bao03]

Lichun Bao, J. J. Garcia-Luna-Aceves.

Topology & MAC: Topology management in ad hoc networks.

Proceedings of the 4th ACM international symposium on Mobile ad hoc networking & computing.

Pg. 129-140. 2003. ISBN:1-58113-684-6.

[Alghamdi05]

Mohammed I. Alghamdi, Tao Xie, Xiao Qin.

PARM: a power-aware message scheduling algorithm for real-time wireless networks.

Proceedings of the 1st ACM workshop on Wireless multimedia networking and performance modeling.

Pg. 86-92. 2005. ISBN:1-59593-183-X.

[Jayashree04]

S. Jayashree, B. S. Manoj, C. Siva Ram Murthy.

On using battery state for medium access control in ad hoc wireless networks.

Proceedings of the 10th annual international conference on Mobile computing and networking.

Pg. 360-373. 2004. ISBN:1-58113-868-7.

[Zheng03]

Rong Zheng, Jennifer C. Hou, Lui Sha.

Resource management: Asynchronous wakeup for ad hoc networks.

Proceedings of the 4th ACM international symposium on Mobile ad hoc networking & computing.

Pg. 35-45. 2003. ISBN:1-58113-684-6.

[Dam03]

Tijs van Dam, Koen Langendoen.

Energy-efficient MAC: An adaptive energy-efficient MAC protocol for wireless sensor networks

Proceedings of the 1st international conference on Embedded networked sensor systems.

Pg. 171-180. 2003. ISBN:1-58113-707-9.

[Jacome03]

Margarida Jacome, Francky Catthoor.

Special issue on power-aware embedded computing.

ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems (TECS) - Volume 2, Issue 3 (August 2003).

Pg. 251-254. ISSN:1539-9087.

[Simunic05]

T. Simunic.

Power Saving Techniques for Wireless LANs.

Proceedings of the conference on Design,

Automation and Test in Europe - Volume 3. Pg. 96-97. 2005.

ISSN:1530-159.

[Bononi01]

Luciano Bononi, Marco Conti, Lorenzo Donatiello.

A distributed mechanism for power saving in IEEE 802.11 wireless LANs.

Mobile Networks and Applications. Volume 6 , Issue 3 (June 2001).

Pg. 211-222. 2001. ISSN:1383-469X.

[Molta05]

Dave Molta.

Wi-Fi and the need for more power.

Network Computing. December 8, 2005.

http://www.powermanagementdesignline.com/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=174909898

[Gruteser01]

Marco Gruteser, Ashish Jain, Jing Deng, Feng Zhao, and Dirk Grunwald.

Exploiting Physical Layer Power Control Mechanisms in IEEE 802.11b Network Interfaces.

Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado at Boulder.

Tech Report: CU-CS-924-01. 2001.

http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/gruteser01exploiting.html

[Chen04]

Huan Chen and Cheng-Wei Huang.

Power management modeling and optimal policy for IEEE 802.11 WLAN systems.

IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference 2004.

http://eeipc3.ee.ccu.edu.tw/teacher/huan/paper/VTC04fall_PS_2099260022.pdf

| ARQ | Automatic Repeat reQuest |

| BAMAC | Battery Aware Medium Access Control |

| FEC | Forward Error Correction |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| LPL | Low Power Listening |

| LR-WPAN | Low Rate Wireless Personal Area Network |

| MAC | Medium Access Control |

| PAMAS | Power Aware Multi-Access Signaling |

| PSM | Power Save Mode |

| RAS | Remote Access Switch |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| WiFi | Wireless Fidelity |

| WLAN | Wireless Local Area Network |

| WMAN | Wireless Metropolitan Area Network |

| WPAN | Wireless Personal Area Network |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

Note: This paper is available on-line at http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain.